The end of an era.

The 2023 Enderle & Moll wines have arrived; this will be the last vintage.

This short essay is I guess my small tribute, a sad goodbye. This is one final effort to give these two the credit they deserve and to say thank you for the wines they shaped, the culture of German Spätburgunder they changed.

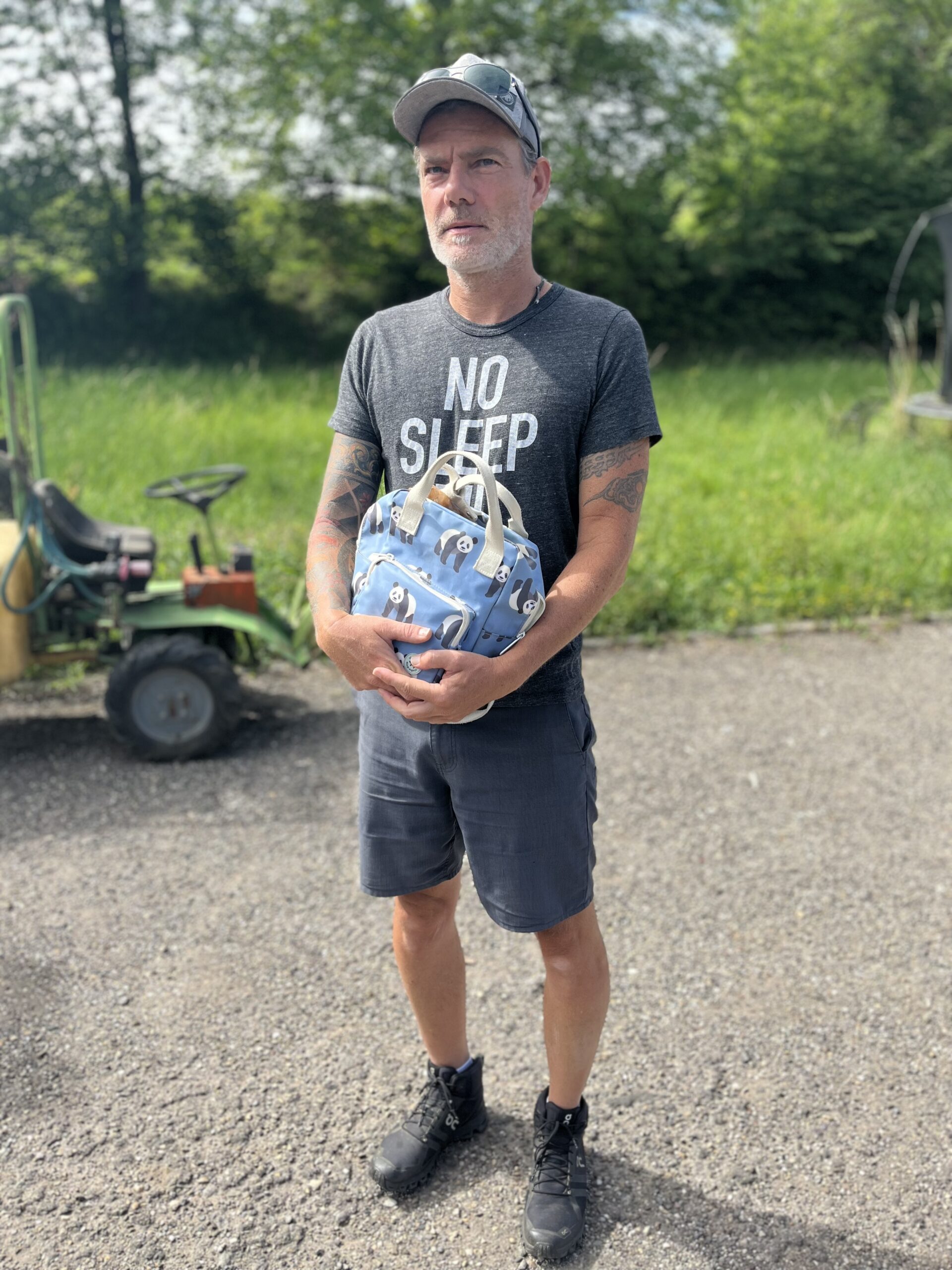

For me, Sven and Florian started, pictured above in a photograph from 2014, marked, and perhaps changed, the course for German Spätburgunder for the next decades.

When I first tasted these wines back in 2008 or 2009, they were nothing short of a revelation. I remember exactly where I was when I tasted the first one: at the now-defunct Seasonal Restaurant in New York with Dan Melia of the also-now-defunct Mosel Wine Merchant. He had brought a bottle of the 2007 Enderle & Moll to pour. I worked in wine retail at the time and this was Dan’s pitch to myself and my partner-wine-buyer at the time Joe Salamone. By the end of the meal, I believe, Joe and I had become the first buyers of Enderle & Moll in the U.S.

For me, and for Joe I think, when we tasted these wines the needle jumped the groove and the music stopped; the mic dropped.

Enderle & Moll had found the path forward.

I think back to the early 2000s, to years of tasting German Spätburgunders with great curiosity (and, it must be said, most often with great disappointment). Enderle & Moll was the first estate I tasted that so clearly offered a counter-narrative to what most Spätburgunder was at that moment.

Where most German Spätburgunder valued dense color, extraction, smooth, round edges and voluminous textures, Enderle & Moll’s Pinots were alarmingly light in color and extraction, and often times angular and structured.

In a world that valued plush, ripe fruit, Enderle & Moll seemed to focus on soil tones, bramble, herbs, minerals.

When most growers in Germany hadn’t really heard of natural wine, or had nonchalantly dismissed it, Enderle & Moll quickly and instinctively found the value and insight to be had here, taking from this movement many of the ideas that are now unquestionably accepted by even the most “classic” of contemporary winegrowers: a focus on selection massale, vine age, organic or at least very thoughtful farming, a more delicate élevage, a more considered curation of quality barrels, often used, often from Burgundy, bottling unfined and unfiltered when possible.

In a German Spätburgunder world that still seemed to focus on ripeness above all, on late-harvesting to produce the biggest wines possible (“Spätburgunder Auslese Trocken” if you will), Enderle & Moll focused on the quality of the site and didn’t seem to care at all about the potential or finished alcohol.

As an aside, they also applied these red-winemaking techniques (skin-contact, etc.) to the white grapes they farmed and bottled these, hmmm, what would I call them? Skin-contact wines with an orange-ish hue? This was ten years before “orange wines” would become a category. I had never seen nor tasted white wines with such texture and structure outside of Friuli. Unlike most Friulian wines, however, they bottled their whites in clear bottles, flaunting the orange-wine colors.

These are just the facts.

Now, I’m not a winemaker. I don’t live in Germany full-time. I can’t honestly speak of how influential the wines of Enderle & Moll were. They seem to get a lot less credit than the micro-production wines of Henrik Möbitz, for reasons I don’t quite understand. Möbitz’s wines were lovely; I met with him and tasted his wines extensively back in the day. I climbed the ladder down into his micro-cellar. Yet Enderle Moll, it seems to me, produced much more wine, of a very similar quality level, over a longer period of time.

Regardless, in the end I can’t speak directly to the influence of either of these growers. Did other winemakers sit alone in their kitchens, tasting these wines and comparing them to their own Spätburgunder-Brunellos only to reconsider their ways? Probably, some, yes.

I’m also sure many German growers just found a similar path, a similar style, without knowing much or anything about Enderle & Moll. Much of this was “in the air” as one might say. The Germans have this lovely word: the Zeitgeist.

What I am saying, however, is that Enderle & Moll seem to have found this place, this style, a good two decades before even some of the greatest winemakers in Germany.

For this Enderle & Moll deserves a rather hallowed place in the story of German Spätburgunder. To some degree, it’s as simple as that.

The fact that these wines are, nearly twenty years later, still among the most clear and transparent, the most soil-driven, the most unique Pinots made in Germany only adds to this legacy.

Yes, over the years many things changed at this estate: Florian Moll’s initial partner Sven Enderle left in 2019. This wasn’t easy for either of them, and as good friends of both of them, I made the decision not to discuss it openly. It was not a happy breakup; fingers were pointed both ways. It felt like a personal story; it felt like it was not my story to tell. Maybe this was a mistake. I wasn’t looking to cover up any great transgression, I was trying to protect both of my friends.

For me, having tasted the wines every year since the beginning, and having indulged in the last few days of all the 2023ers that have arrived, I must say I never noticed any big change, any consistent or noticeable dip in quality. It must be said, about Enderle & Moll’s wines and many more natural wines, there is just a level of inconsistency one must expect. I think it’s a bit simplistic and dishonest to say that either person had the exclusivity on talent, or taste, or labor. Those that do trade in these ideas are normally trying to sell something else.

I guess I’m just too old to believe in any simplistic narrative. Humans, alone or working as a team, are complicated. Wine is complicated. That’s also its saving grace.

In the last few years Florian has had problems arranging for a new cellar team, for more constant and dependable labor. It all became just too much work for one person, for Florian. And there were other, completely random incidents that put the whole project in serious financial stress, like a warehouse that went bankrupt while holding a good amount of their wine. This wine, most of it sold, became completely inaccessible. Then in 2024 there were horrifying frosts that destroyed nearly everything. I think it felt to Florian, in a way, obvious. This was the end.

There is always something positive in the conclusion of any narrative; and of course always something sad. Something we loved, it is no longer.

Yet, as we begin to sell the final chapter, I want to focus on one of the things I loved most about these wines: They remained, always, singular and canonical, while also being for the most part available and fairly priced.

For me, Enderle & Moll occupy a sacred realm not unlike Clos Roche Blanche back in the day, the wines of which I would nonchalantly buy over and over again without a thought about “collecting” or “aging” or any sort of speculation. They were simply wines to open and to enjoy; they were thrillingly honest, delicious. They had soul and character.

To the very last drop, this is also Enderle & Moll. Thank you Sven and Florian, for everything.