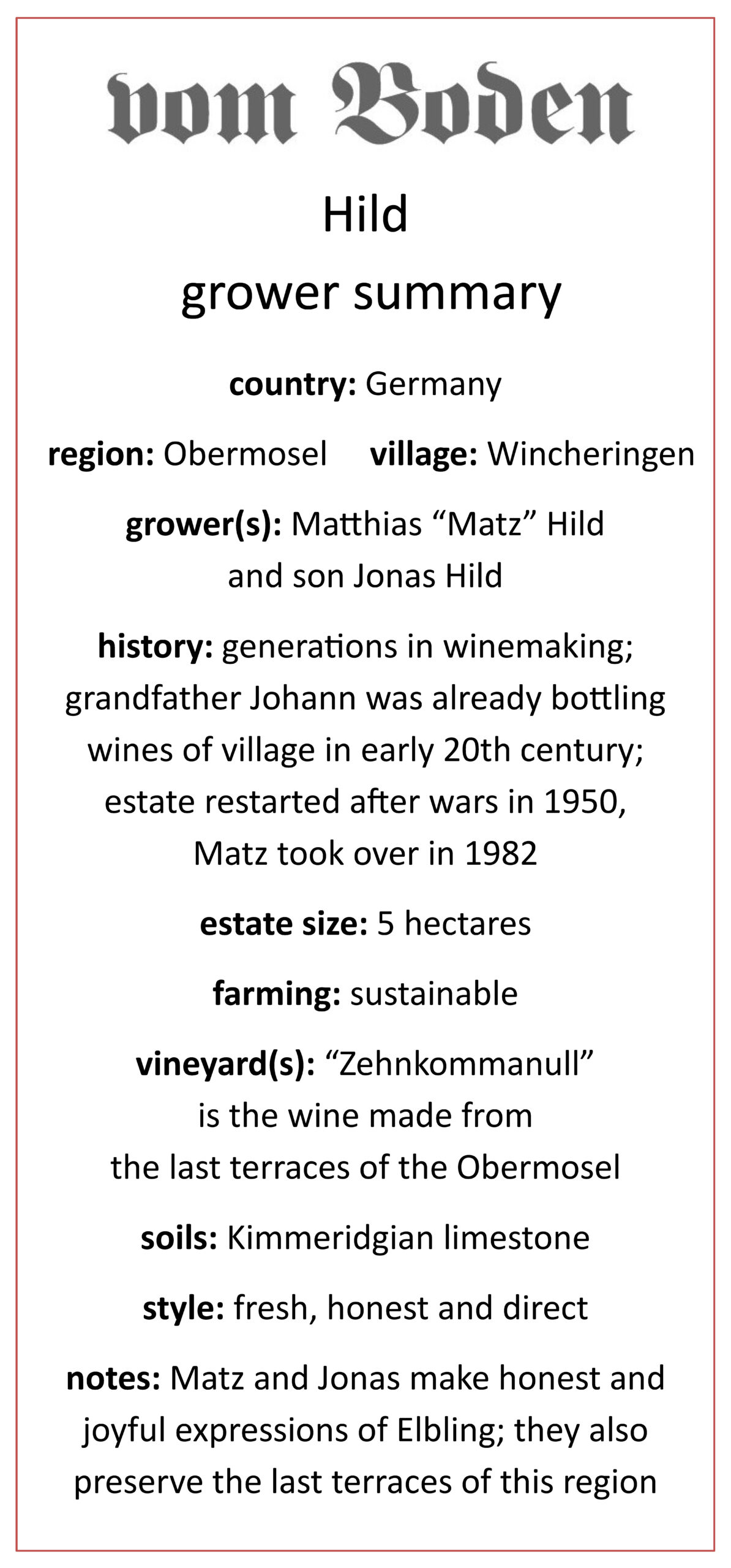

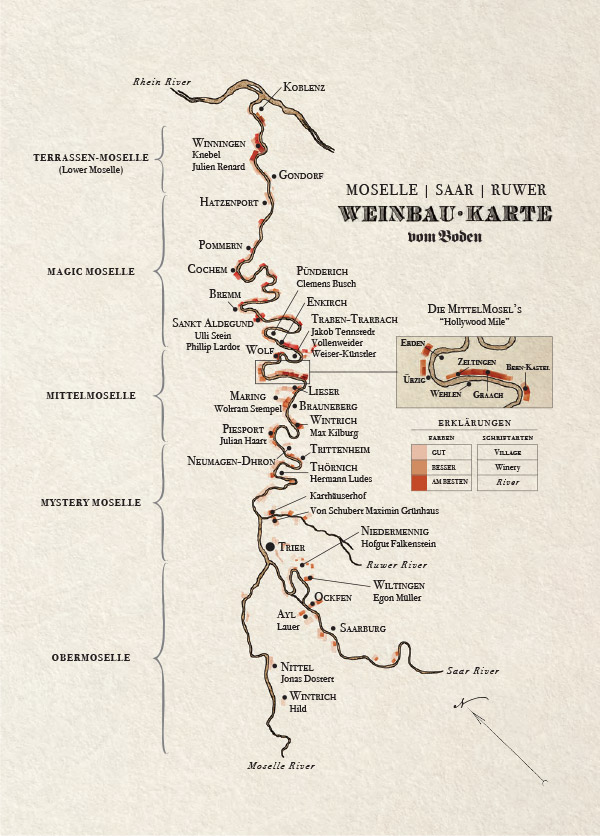

Maybe you’ve never heard of the Obermosel, or Upper Mosel.

I really hadn’t either, when I first visited over a decade ago. I mean, I knew it was there. I just didn’t know what was there.

As it turns out, what is there has nothing to do with everything we’ve ever been taught about the Mosel. In other words the Obermosel has nothing to do with Riesling and nothing to do with slate. Instead, we find limestone. The Obermosel in fact represents the beginning of the Paris Basin, the geological reality that informs places like Chablis and Sancerre.

Instead of Riesling, in the Obermosel we find a winemaking culture based on one of Europe’s oldest grapes: Elbling.

Elbling feels like more than a grape here. It’s not quite a religion, but it is a significant part of the culture, a regional dialect that is spoken through this wine of rigorous purity, of joyous simplicity, of toothsome acidity. Even at its best, Elbling is not a grape of “greatness” as much as it is a grape of refreshment and honesty and conviviality.

The comparisons are plenty, though none of them are quite right: If Riesling is Pinot Noir, then Elbling is Gamay. If Riesling is Sauvignon Blanc, then Elbling is Muscadet. You get the idea.

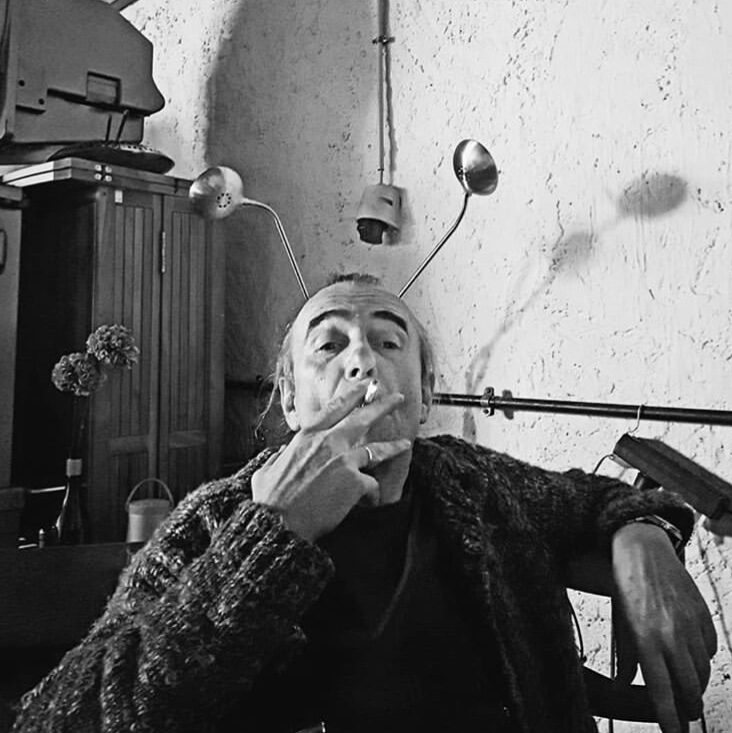

The joy of Elbling is the uncompromising vigor and energy, the raucous and super-chalky acidity. Matthias Hild (pictured above) and his son Jonas farm about five hectares in the sleepy town of Wincheringen. “Matz,” as he’s known to friends, told me that back in the 1980s, when he’d have an Elbling clock in at less than 8.5 grams acid, he’d taste it and question if it was Elbling at all.

Which is sort of like saying you’re not sure the music is loud enough if your ears aren’t bleeding.

Matz is a curious mix of scholar, advocate, farmer and trickster. He sports a thinning pony tail, squints and sizes you up a good amount. He smiles a lot, especially as I’ve gotten to know him over the years. He is a strong person; the entire family, his wife Dorlies and both of their children, have a certain solidity to them.

I would imagine it is this strength of character that explains, at least in part, how the Hilds have survived in the Obermosel making quality-minded, honest wines in a region where this is not a financially wise thing to do.

The fact that Matz and Jonas single-handedly are trying to save the old, terraced parcels of Elbling (see photo directly above) is a move that is equal parts romantic and completely insane. The financial realities of working these vineyards by hand while accepting their lower yields simply do not add up. This is an act of cultural preservation more than anything else.

Matz and Jonas call the Elbling made from these terraces the “Zehnkommanull” which means simply 10% – the wine normally ferments bone dry and ends up 10% ABV or less. The few cases that I’m able to get of this wine are, to me at least, semi-sacred voices of a time long past. Sacred voices that end up on the $20-and-under table and most often overlooked.

Slowly, over the past decade, people have noticed. What I truly thought would be a passion project, an act of scholarship and education and advocacy, has turned into a good little business. It turns out people do value deliciousness and value.

One of the greatest problems wine has had over the last twenty years is that it forgot this – it became a luxury product.

Well, here’s to real wines of place, of history and singularity, that you can actually afford.

If any of this interests you, you can take a look at our Obermosel journal 008: you can view here. It provides maps, pictures and a history of both this part of the valley and the Hild family.