“Lauer has gone cult.”

I keep the quote above largely for sentimental purposes.

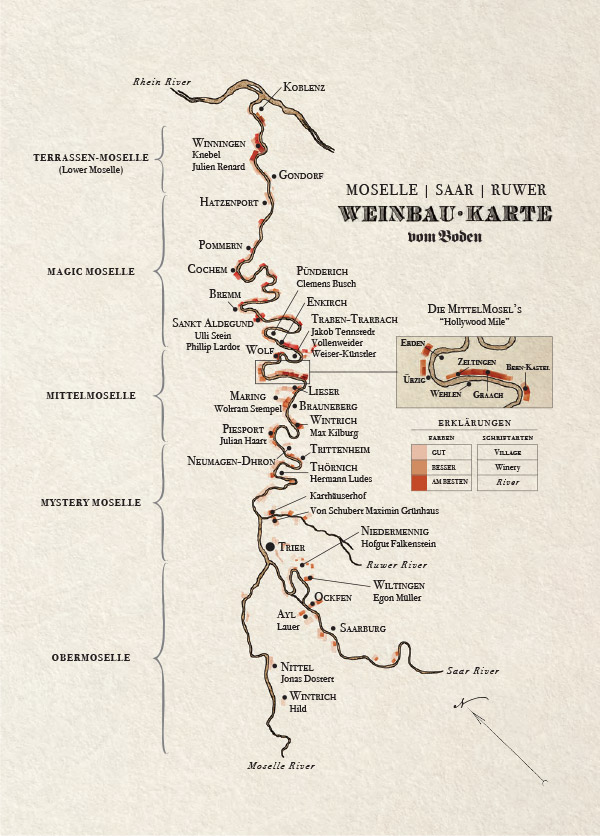

It was first penned by me, in the summer of 2011, as I was trying to come to terms with the stratospheric rise of Lauer, who was then still a bit of a newbie on the U.S. wine scene. It’s funny to read now as Lauer has been, unquestionably, established as one of the greatest addresses in Germany.  For purists, there is nothing like the Saar. It is arguably one of the greatest, most unique wine-growing regions on earth. The core of greatness in the Saar is intensity without weight, grandiosity without size.

For purists, there is nothing like the Saar. It is arguably one of the greatest, most unique wine-growing regions on earth. The core of greatness in the Saar is intensity without weight, grandiosity without size.

Frank Schoonmaker, my hero, put it best in his 1956 tome The Wines of Germany: “In these great and exceedingly rare wines of the Saar, there is a combination of qualities which I can perhaps best describe as indescribable – austerity coupled with delicacy and extreme finesse, an incomparable bouquet, a clean, very attractive hardness tempered by a wealth of fruit and flavor which is overwhelming.”

Yes, this is the Saar and Florian Lauer is currently one of the greatest winemakers in this sacred place.

ENJOY THE LAUER IMMERSION EXPERIENCE, above – NOW ONLINE AND AVAILABLE TO ALL!

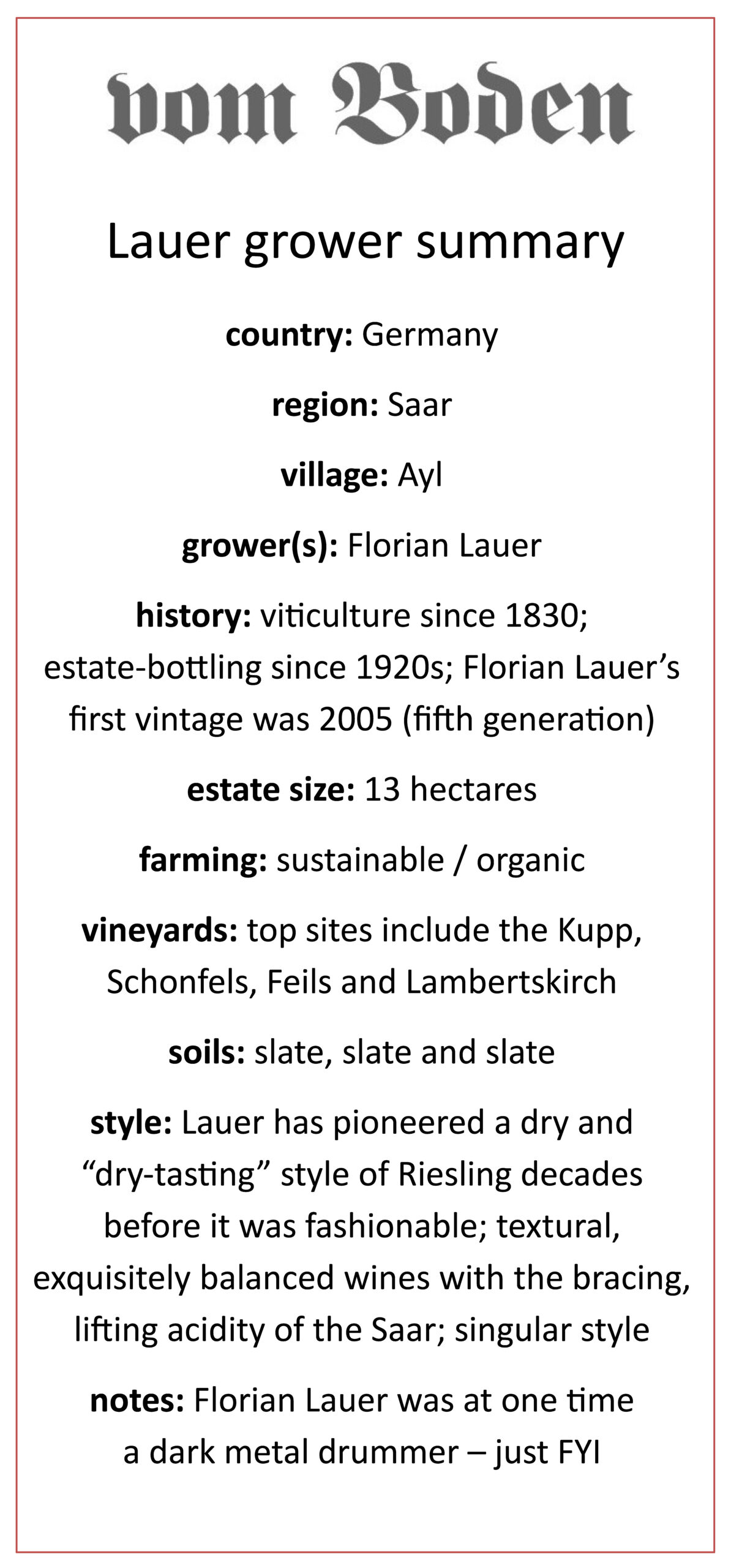

Florian’s general style is exactly the opposite of his famous Saar neighbor Egon Müller. At Lauer, the focus is on dry-tasting Rieslings as opposed to the residual sugar wines of the latter. For this style, there are really only two addresses in the Saar (though more come online every year, trying to chase the style): Lauer and Hofgut Falkenstein.

Employing natural-yeast fermentations, Lauer’s wines find their own balance. They tend to be more textural, deeper and more broad-shouldered. They have a preternatural sense of balance, an energy that is singular. Yet the hallmarks of the Saar are there: purity, precision, rigor, mineral.

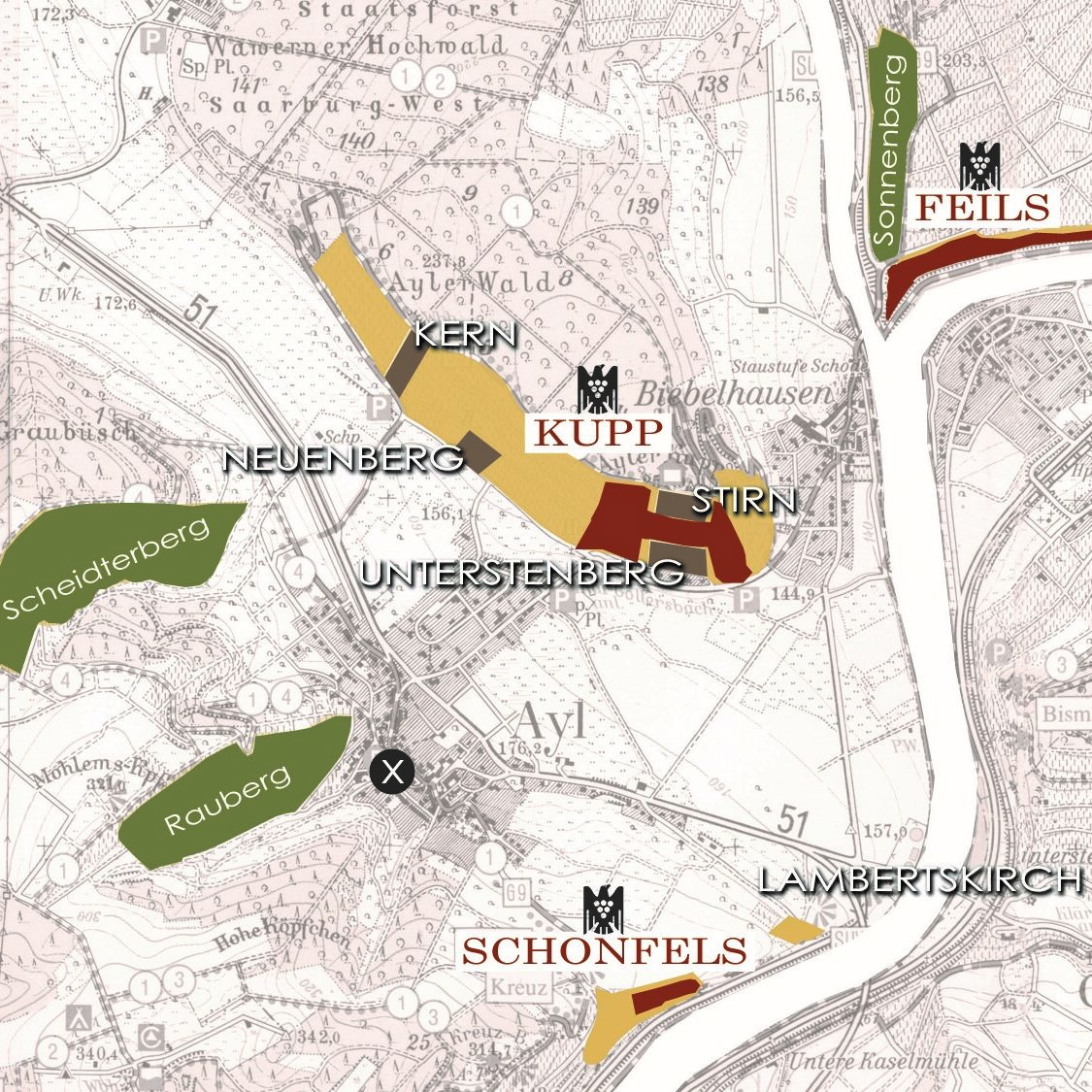

Florian’s playground is the breathtaking hillside of the Kupp, pictured at the top of the page, with a map of the area directly above. Though the many vineyards of this mountain were unified (obliterated?) under the single name “Kupp” with the 1971 German wine law, it has been Florian’s life’s work to keep the old vineyard names alive, to keep these voices alive. He has been fighting this fight since his first vintage in 2005 and only with an update to the law in 2014 can he now legally use the older vineyard names such as Unterstenberg, Stir, Kern and Neuenberg.

Florian fought the law, and he won.

In addition to the expanses of the Kupp, Lauer farms three other important sites, Feils, directly across the river, and the precipitous, cliff-vineyard Schonfels, a bit upstream from the other two sites and, finally, the once-famous Lambertskirch, just a stone’s throw from Schonfels. This was a site with a huge reputation in the 19th and mid-20th century, yet it was abandoned. Lauer cleared the site and replanted it himself.

For an even more in depth overview of the Lauer vineyards, check the video below with an in depth description touring these sites via Google Earth.

At the very bottom of the page, the tabs discuss all about Florian’s various bottlings. If you’re nutty enough to read all this stuff, you’ll graduate with your PhD in Lauer. It’d be great if you’d then go and explain it all to your friends.