Hammelmann’s vineyards were only good for onions and potatoes.

At least that was the refrain, most likely said with more than a touch of disdain, for the cold, flat, wind-swept Rhein basin of the Pfalz, where Hammelmannn grew up. Zeiskam is the name of the town. You’ve never heard of it, I’d guess. We hadn’t either.

Regardless: Much of what Lukas heard growing up was this quip about Zeiskam and its onions and potatoes.

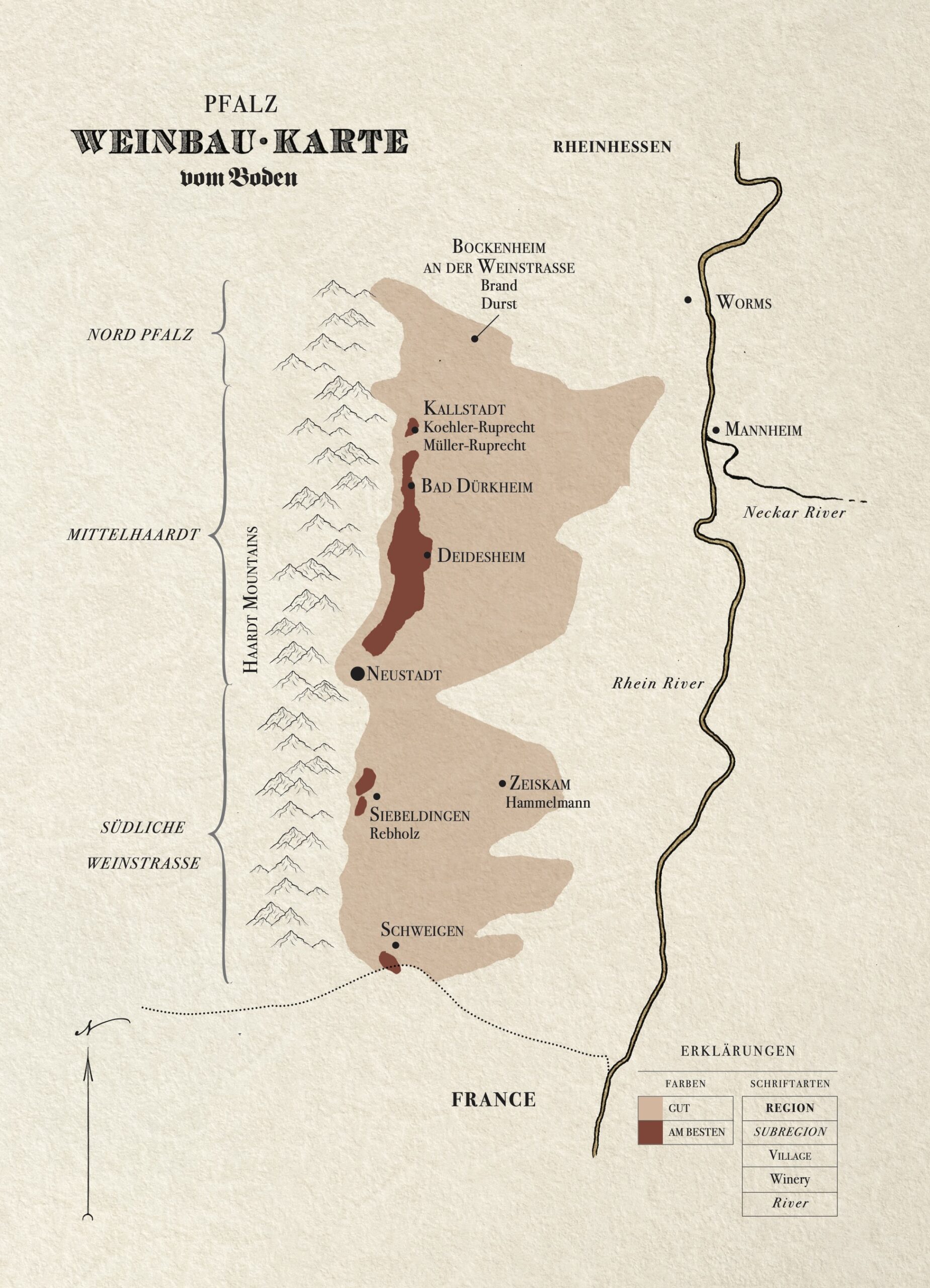

Zeiskam was nothing more than potato-berg. For that “good” wine, well, you had to go twenty minutes west, to Rebholz’s southfacing sites, warmer and sheltered in the Haardt hills. Or, better yet, for that aristocratic juice you had to drive a half-hour north to the famed “Mittelhaardt,” to the towns of Bad Dürkheim, Forst and Deidesheim.

For the American wine love, I think the stature of the middle Pfalz eludes us, with its wealth and pomp. The central Pfalz, what the Germans call the “Mittelhaardt,” is something like the Germanic Napa Valley. There are grand estates and manicured lawns and shiny cars driven by people with expensive taste in eyewear. (Want to learn more about the Pfalz as a region? Click the button to the right: “Learn more about the Pfalz.”)

There are a lot of “vons” in the Pfalz – the aristocrats, das old money. More than a few investor-types have invested money here, the new cash bulking up the old money. The “new” and the “old” have different cultural contexts of course, but this general recipe book probably sounds pretty familiar to Napa, non?

For a German, the middle Pfalz is fancy and when you come from the periphery of the Pfalz itself, there is something of a divide. The Mittelhaardt is for wines of breed and distinction and Zeiskam is for onions and potatoes. These are just lines you don’t cross.

Until someone like Lukas Hammelmann comes along and says something like: “Fuck you, line.”

I first tasted Lukas’ 2019ers in the summer of 2020, when all I did was receive pallets of wine from Europe and taste them alone in my kitchen. Goddamn that summer of never-ending quarantine. I tasted so many – so many – bottles that year, samples sent from everywhere in Germany. Many were forgettable; that’s just how it is in this business.

But I never, ever forgot Lukas’ wines.

They made such an impression on me that I went to visit him in August of 2021, while COVID was spiking. I just couldn’t wait. I have since tasted six vintages and with each passing year I am just as startled, just as invigorated, just as blown away and even more confident than I was years ago that Lukas is a rare and blazing talent.

The Rieslings are absolutely screeching and they soar across the palate with raw citrus, green herbs and a bone-chilling acidity (more than one taster has confused Hammelmann’s wines with the Mosel). These wines rip.

They are ruthless and in the first months as I tasted them they reminded me quite a bit of Schäfer-Fröhlich, though Hammelmann’s wines are perhaps punchier, more rustic and raw. While Hammelmann direct-presses, preserving the fierce acidities, most of the wines are aged in oak barrels, many of which are on the newer side. This is not an aesthetic choice – he’s not looking for oaked Rieslings – he simply wants very specific barrels and he wants to know the provenance. This one can only do with new barrels. Yet the combination of this ultra-high-toned fruit (raw citrus, lime zest, orange oils) and the subtle undercurrent of wood creates an effect that is minty and herbal. I find it incredibly appealing. Most of the Rieslings are bottled unfined and unfiltered so they can have a saline, leesy quality. I also find this incredibly appealing.

His Chardonnays in the last few years have simply blossomed; the 2023ers, the newest releases, just have to be among the best Chardonnays I’ve had from Germany. Hammelmann is refining his style; the barrels are aging. It is a profound development.

One can find very rare examples of Pinots with clarity and angles; there are even rarer examples of these Pinots as sparking wines, a blanc de noirs and a rosé are out there and superb.

Regardless of what you may think of the wines, the style is singular. These wines are unique to Hammelmann, unique in the Pfalz. Maybe you like them, maybe they are too much for you, regardless the quality is indisputable.

So the question, then, is this: How in the hell are these wines so good?

According to the VDP map above, all the “famous sites” of the Pfalz are to the west, up into the Haardt mountains – all those purple and red squares. Not only are there no vineyards of note around Zeiskam (which you can see listed to the right of the green “Pfalz” in the center of the image), the area isn’t even highlighted green. The VDP map shows it all as a part of that unpleasant industrial gray; it doesn’t even look like there’s a damn green lawn in the town. (Fact: I have been there and there are plenty of lawns and vineyards.)

In many ways, it makes no sense.

Yet in other ways it makes perfect sense. Lukas has said these site, these two neighboring villages (his hometown of Zeiskam and then Hochstadt, directly west) were historically too cool for great viticulture. We’ll discuss the confusing microclimates in a bit, but this is a trend we’re seeing all over the world: sites once too cold are now in the zone.

That said, I do think that for Hammelmann there are two other factors at play, both of them entwined within the other: determination and originality.

First, Lukas is just something of a force. I don’t think he’d have been able to accomplish what he has accomplished without simply willing it to be. Even the way he speaks; he says things he believes as if they are a well-known fact that you should have already known. He believes Zeiskam was overlooked and ridiculed by people. He believes the terroir could be great… and now somehow it is.

Second, originality: In many places in Germany (or any old and famous winemaking culture) there is the tendency to copy, to emulate. I don’t mean this in a pejorative sense. Very often such emulation is a reflection of a belief in a Platonic ideal, or a respect for tradition.

Hammelmann, for better or worse, is so completely on his own path that reference points for the first-time taster are hard. As I mentioned, there is something of the force of Schäfer-Fröhlich (whom Hammelmann very much likes), something of the glaze and power of a more traditional Pfalz winery (say of Rebholz or of Christmann), yet also something of the acid-as-everything philosophy of a Weiser-Künstler or a Jonas Dostert.

The wines see extended lees contact and are normally bottled unfined and unfiltered with lower levels of sulfur, so there can also be something of a natural-wine aesthetic, though this is not to imply that they are not crystal clear. The wines read much more classic than they do natural. (We have a more detailed conversation of the winemaking below.)

The wines are just totally unique.

For me personally, after nearly two decades of scouring Germany, stops this fascinatingly new and complex and beautiful and thrilling are not all that easy to find. And when you find them, you stop and pay attention.