I will refer to the Mosel as the “Moselle” in this essay, in homage to the legendary early- and mid-twentieth century connoisseur, importer, and author Frank Schoonmaker, who referred to the Mosel using the French term “Moselle” in his legendary 1956 tome The Wines of Germany. At the time, for reasons I don’t truly understand, it was common for English writers to use the French term. Thank you for your forbearance.

The Moselle is one of the oldest winemaking cultures on earth.

When the Romans were putting the limestone finishes on the Colosseum around A.D. 80, there were likely Romans in the Moselle, building walls out of slate to cultivate these cliff vineyards. The city of Trier — the main city of the Moselle and the oldest city in Germany (also the birthplace of Karl Marx) — was the northernmost outpost of the Roman empire; it was called Augusta Treverorum.

It’s wild to consider, but Trier, in Roman times, was almost as big as it is today. Around A.D. 300, the population is estimated to have been 65,000+. Today it is about 100,000.

It is the Moselle River, with its extreme contortions and 180-degree hairpin turns, that has shaped some of steepest and most dramatic vineyards in the world, all of them infused with history and lore. You can’t spit without hitting a Roman press house or an abbey founded in the Middle Ages.

Walk through any of the villages and you see markers over the doors of the timber-framed homes, casually declaring “erbaut 1560” — built in 1560 — or some such incredibly deep history, at least for most Americans. Behind these quaint villages rise vineyards that, at their most severe, resemble fortresses; their sheer scale and verticality seems to transcend human ability.

The Moselle is a Stonehenge, magic and ancient and mysterious and improbable if not simply impossible.

The Moselle is a mythical realm; yet there it is. For me, this valley is one of the most beautiful places on earth; how it is not as famous as the Grand Canyon I genuinely do not understand. Given the cultural history here, how this place is not a UNESCO World Heritage Site truly baffles me.

For many Americans, the Moselle is what we think about when we think about German wine. Germany’s most famous vineyards are in the Moselle, with names both poetic and evocative: Sonnenuhr (sundial), Würzgarten (spice garden), Goldtröpfchen (little drops of gold), and Himmelreich (kingdom of heaven), to name but a few.

The Moselle is a mythical realm. Yet there it is.

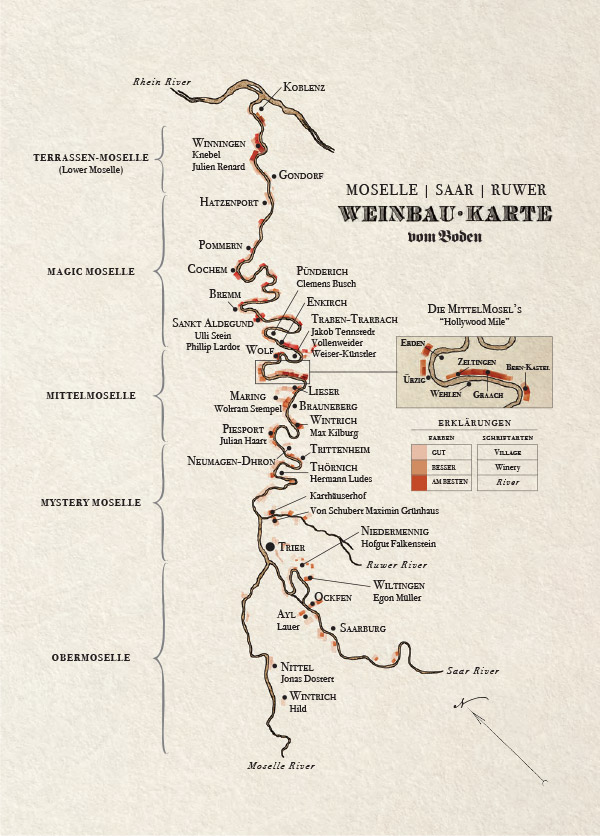

Legally, “the Mosel” as a wine region includes the vineyards on the Moselle proper as well as the vineyards on both the Saar and the Ruwer Rivers, two small tributaries of the Moselle. This bureaucratic efficiency is a lie; it is total bullshit and I will not comply. The Saar and the Ruwer are wildly distinct places. They are unique appellations; if you want to read more about the Saar please see Lauer’s grower profile.

While books will say there are roughly 9,000 hectares being farmed in “the Moselle,” this number includes both the Saar and the Ruwer. In reality, there are only around 7,700 hectares being farmed in the Moselle, another 800 hectares in the Saar, and only 200 in the Ruwer. In total, therefore, we are somewhere just below 9,000 hectares. These three appellations, together, are roughly three times as large as the Rheingau (around 3,000 hectares) and more than twice as large as the Nahe (with around 4,000 hectares). Yet the Moselle, Saar, and Ruwer are dwarfed by the biggest wine regions in Germany, the 25,000-plus hectares of the Pfalz or Rheinhessen.

I don’t think these numbers are particularly important, mind you, but most books seem to begin with facts like this, and maybe it’s interesting or relevant to offer this sense of scale?

The Moselle is famously one of the coldest wine regions on earth; this is the Canada of Europe, to employ an absurd if useful analogy. Trier is at roughly the same latitude as Winnipeg. A Moselle (by which I mean a bottle of wine from the Moselle) is lightness incarnate, yet it can be a lightness with an ornate quality, with a dapple of the Baroque. There is a ripeness that can flirt with the tropical, with the essence of warmth, yet it is always countered (or should be) by a pushing, almost (but not quite) overpowering acidity. A great Moselle should always be a complex yet perfect expression of balance.

We are told that the residual sugar very commonly associated with Moselle wine (one of many misconceptions) is often necessary because of the bracing and cruel acids. This simple story of off-dry Riesling is somewhat true — sometimes. Yet this explains only part of the story, because there have always been dry wines from this place. In fact, in the late 19th century the Moselle was perhaps more famous for dry Rieslings than off-dry. Regardless, these days there are more dry wines from the Moselle and they are becoming more and more convincing.

So the question remains: If the Moselle is one of the colder wine regions in Germany, why is this? What are the specific geographic and structural factors that make this so? The Moselle River is flanked on both sides by high plateaus: On the western side is the Eifel, on the eastern side is the Hünsruck. Both of these places are rolling hills topped by dense forests and, in some places, open agricultural fields.

Cold winds batter these regions, and these cold winds descend into the Moselle through a multitude of side valleys. (Because of this intrusion of cold air, it is very often the case that the wines from vineyard sites in these side valleys, further away from the warming influence of the Moselle River, have more bracing acid structures. In the simplest terms: The further away you are from the Moselle, the colder the site is.)

The depth and narrowness of the Moselle Valley is both a limiting factor and its saving grace. The narrowness and severity of the valley means that the steep slopes are perfectly angled to catch the sunlight. But, historically only the most perfectly exposed sites, those facing due south, could achieve proper ripeness.

On the other hand, the depth and narrowness of the valley also protects. The large Moselle River (whose size and thus warming influence has been increased with the dam system that was installed in the postwar period) functions as a serpentine heater for this cold place, reflecting the light and the heat. In some ways, maybe it’s useful to think of the river as if it were a long, curving floor register in a forced-air heating system, sending warm air up through the valley. The relative narrowness of this place means that these warm air currents keep at bay some of the cold winds from both the Eifel and the Hünsruck. The cold air that doesn’t sneak in through the side valleys simply blows right over, buoyed up by the warmer air rising off the river.

In this curious way, the Moselle (especially the vaunted Mittelmosel and its “Hollywood Mile,” as I call it) is both a “cold place” and a “warm place.” When people speak of the wines here, the most commonly cited quality is the lightness, the delicacy — that is the cold. Yet Moselle wines, especially Mittelmosel wines, can also show a sometimes surprising opulence of fruit — that is the warm.

We are talking wine, though, so obviously the devil is in the details. Each village and indeed each vineyard has its own signature; even the famous slate of the valley changes constantly. To add yet another layer, the voice of the winemaker adds a final flourish. Thus we have Moselle villages such as Thörnich or Traben-Trarbach. Both are considered very cold. The profiles of the wines here tend to have more to do with the Saar than the Moselle in that they are slimmer, more mineral, more austere and acid driven.

Then, some miles upstream, we have the village of Piesport with its famous Goldtröpfchen. This mega-amphitheatre is about as warm as it gets in the Mittelmosel. It is a wall of vines, mostly southern facing; the warmth of the river is right there. Yet the magic of some growers here, like Julian and Nadine Haart, is that they manage to condense this opulent ripeness into something profoundly deep, true to the exoticism of this place, yet with an incisive form and undeniable precision.

Like mad alchemists, they turn the warmth not into tropical fruit, but into a vibrating, cool-toned energy. Again, it is the village and the vineyard, but it is the village and the vineyard as interpreted by the grower.

Yet the fact is that this varied landscape shares a common general form — a Moselle is a Moselle is a Moselle. This is the lore and the magic. The wildly diverse and complicated landscape, the nuance and range of expression possible from this single corner of the world, that is the fascination, the obsession…the beauty. This is why there have been thousands of books written about this place, all of us trying to capture some fleeting truth, something essential about why it is so sacred.

While the Burgundian comparison is liberally thrown around the wine world, the Moselle is to my mind one of the few places where this comparison is warranted, maybe even necessitated if you really want to understand the region. The Moselle is a sort of mirror to Burgundy, and vice versa. Both regions had very strong monastic cultures for many centuries. These cultures slowly and painstakingly articulated the nuances of terroir, defining and naming the vineyards.

Here, as in Burgundy, the vineyards have in many cases stronger reputations than the growers who work them. Both regions stake their reputations on a mono-variety wine culture: Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in Burgundy, Riesling in the Moselle. So while it may be a bit intellectually lazy to compare Burgundy to Germany as a whole, I think there are very serious arguments to be made that Burgundy and the Moselle are true siblings.

It’s a fascinating duality, but while in the U.S. and the U.K. the Moselle is one of the most vaunted wine regions on earth, in Germany the Moselle is often seen in a different light. As an outsider, an American, it’s hard to articulate the situation exactly, but my sense is that perhaps the Moselle is seen as somewhat provincial? Less sophisticated? A bit of the country mouse to the Rheingau, Rheinhessen, and Pfalz’s city mouse?

Drive through the famous towns in the Pfalz’s Mittelhaardt and you’ll see a traffic jam of rather large Audis, BMWs, and Mercedes lined up at rather fancy-looking estates. There are manicured lawns, maybe some fountains. The people visiting these estates have expensive looking eyewear; their clothes have been recently pressed. With some rare exceptions, you do not see this caliber of eyewear or dry cleaning in the Moselle. Instead of big fancy cars, you see a lot of old and small Skodas and Opels; you see even more RVs.

This is another fact of the Moselle that I think Americans miss. For many Germans — for many Europeans at large — the Moselle is just a very long and winding campground. That is its main claim to fame.

For miles and miles along the Moselle, people sit on folded chairs in flat, grassy RV parks, the men shirtless, basking lazily in the sun. Above them, behind them, all around them are some of the greatest vineyards on earth. Few of these tourists seem to care much. For them, the vineyards are a nice backdrop to the peaceful river.

It’s a beautiful place, and it’s not expensive. That’s enough.

In other words, part of what makes the Moselle so complicated is the nose-in-the-air wine connoisseurship flanked by sausages and water skiing.

It’d be something like having an amusement park right next to Vosne-Romanée, so that all those well-heeled visitors, recently deplaned from their private jets, had to take in the majesty of Romaneé-Conti within earshot of screaming kids, whiffs of cotton candy, and the sound of diesel generators.

The Moselle is unquestionably rustic, with small hotels and pensions that have rarely been updated over the last three or more decades.

Summer here is the “high time” — your average Moselle winery probably sells most of their wine quite cheaply to these European tourists to help them wash down their döner kebab and currywurst.

For a region steeped in history and agriculture, the scarcity of a more thoughtful casual food scene is notable, even though this is changing quickly. In the winter, the valley is empty. If this stillness is profound and refreshing, it also speaks of a land without obvious opportunity.

I personally love this duality, the raw and the refined, but it has without a doubt hurt the Moselle as a destination. Those suburban neighbors who “collect wine” and will tell you (over and over again) about their trip to Tuscany have never been to the Moselle and have likely never heard of it.

All for the better, honestly.

I would submit it is the crudeness of parts of the Moselle that has saved it. It has kept many people away; it has allowed this place to retain the authenticity so many places have lost.

And while it’s hard to articulate, exactly, it is very clear that the Moselle, and its people, are just different from all the other winemaking regions of Germany. I’ve never heard anyone remark on this, but the geography must also be a part of this sense of difference, of isolation. Look at a map of the various German wine regions. The Moselle is not that far west; it’s only about a two-hour drive from Frankfurt. Yet it is far off on its own. The Rheingau, Mittelrhein, Nahe, Rheinhessen, and the Pfalz form a tight little clique with the wealthy cities of Frankfurt, Mainz, and Wiesbaden as their northern stars.

Baden, Württemberg, and Franken are a bit more expansive but still a consolidated group in the east, flirting with the wealth of Stuttgart and Würzburg as well as Frankfurt, Mainz, and Wiesbaden.

Only our beloved Moselle is alone.

The Moselle is its own thing, almost being pulled by France and Luxembourg away from the Rhein, away from Germany. The Moselle feels like a culture that, with some historical exceptions, is more oriented inward. All this is to say that while the Moselle is one of the unquestionable cornerstones of western European winemaking cultural history, it is also something of an outsider.

And I would add this important note: I don’t think the Moselaners — the people of the Moselle — would have it any other way. Much could be said about the daunting physical and mental toughness of the growers of the Moselle; we don’t have enough time or space here. This is but a short essay about this sacred valley. But keep in mind this is an impossible landscape to work. Your average steep Moselle vineyard, even one that can be worked by some machines, takes nearly twice the person-hours per hectare as a flat vineyard. Your average terraced vineyard, one in which no machine can be used other than what we’d call a weed whacker, takes over three times as many person-hours per hectare per year — a staggering number, a staggering effort. And we’re not even taking into consideration the lower yields of the Moselle, with its old vines.

When you do consider these factors, you are overall looking at a scenario in which the top Moselle wines are somewhere around three times as expensive to produce when compared to the wines of most other German regions.

I’m not sure the American wine lover — or any wine lover — quite understands and appreciates the severity of the Moselle’s situation, the surreal, almost absurd pricing phenomenon that currently exists.

It is not that the other wines of Germany are overvalued, mind you; it is that the wines of the Moselle are dramatically undervalued. Take note: This is changing, as it should.

For those of us who have been lucky enough to visit the Moselle, I wonder if some of our attraction to this place, to these wines, is a reflection of an almost unconscious understanding that to work these sites is a great sacrifice, even if it’s also a beautiful blessing to have a role in one of the greatest and most historic wine-shows on earth. The act of producing wines here — the absolute determination, the faith involved — is as close to a sacred act as we can get in these secular times. We sense this and I think as humans we crave this connection to something so human, yet so much greater than ourselves.

Whatever draws someone to the Moselle, to these vineyards, we can be sure it is not money. It is love.

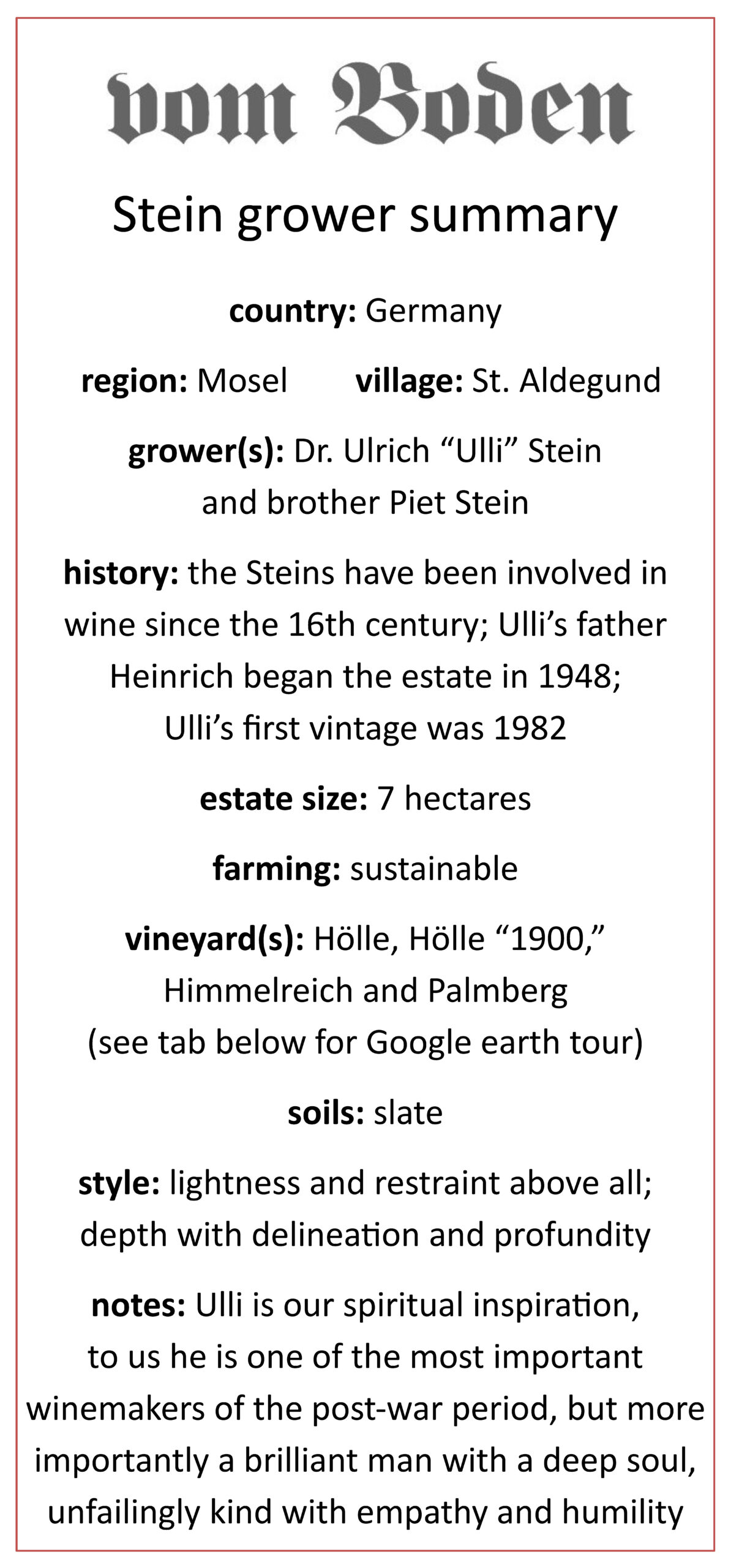

In fact, as alluded to by Schildknecht’s quote above, Stein is more than a winemaker – he is a passionate advocate for the traditional, steep, slate vineyards of the Mosel. In 2010 Ulli published a manifesto warning of the threats to the region’s 2000-year-old viticultural tradition. Dan Melia wrote a beautiful summary of Stein’s manifesto for Edward Behr’s The Art of Eating. The article is reproduced in full, with the kind permission of Edward Behr and Dan Melia: please click the link to the right.

In fact, as alluded to by Schildknecht’s quote above, Stein is more than a winemaker – he is a passionate advocate for the traditional, steep, slate vineyards of the Mosel. In 2010 Ulli published a manifesto warning of the threats to the region’s 2000-year-old viticultural tradition. Dan Melia wrote a beautiful summary of Stein’s manifesto for Edward Behr’s The Art of Eating. The article is reproduced in full, with the kind permission of Edward Behr and Dan Melia: please click the link to the right. It’s perhaps difficult to speak of an overarching “style” at Stein; or maybe it’s that the word, the concept, just doesn’t feel right.

It’s perhaps difficult to speak of an overarching “style” at Stein; or maybe it’s that the word, the concept, just doesn’t feel right.