I’ve had two mind-blowing “wow” moments with German Pinot Noir.

Once with Enderle & Moll, tasting their first release in 2008. And now, with Wasenhaus, tasting their first releases in 2018.

One Spätburgunder revelation every decade, I guess?

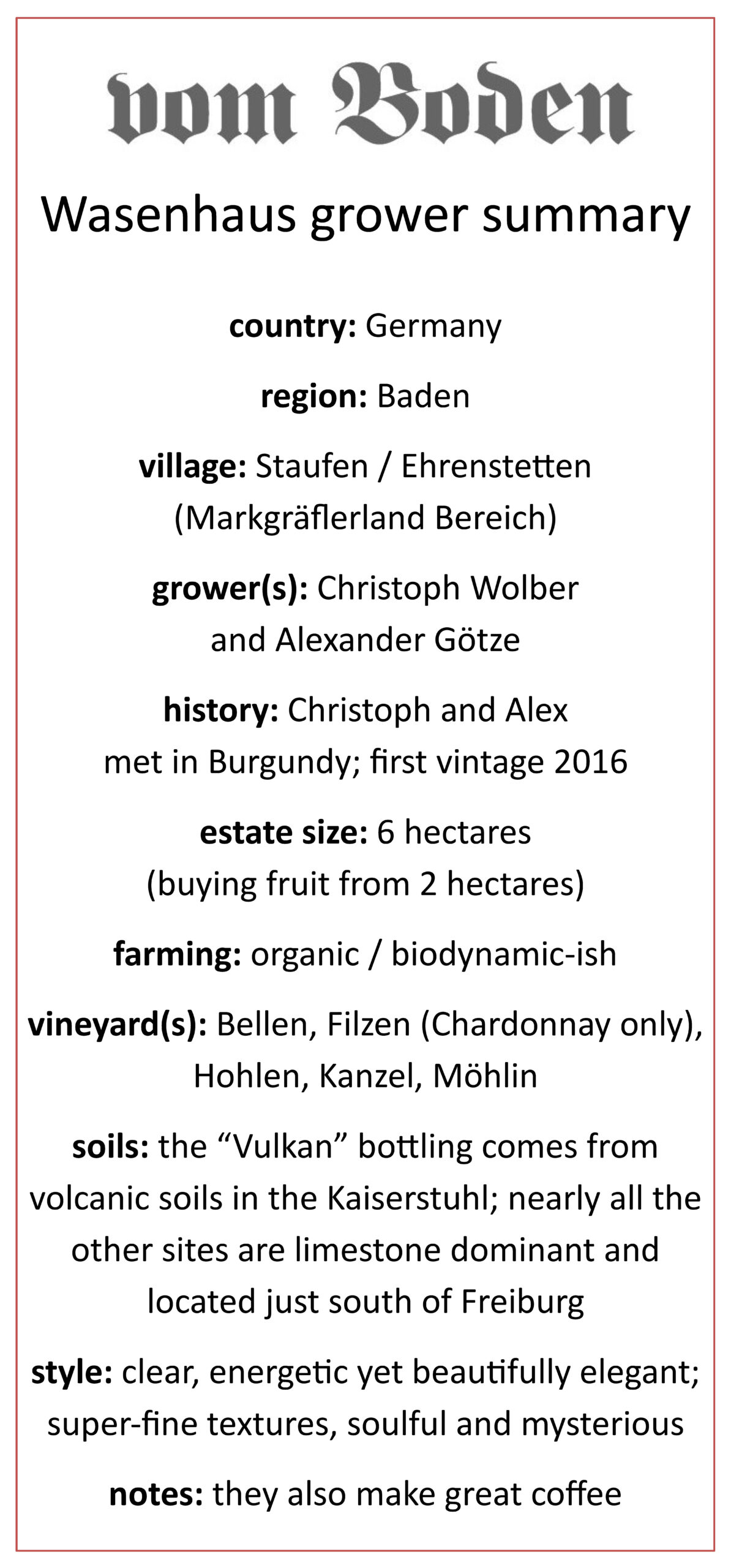

Alex Götze and Christoph Wolber, two Germans, were bitten by the same Burgundy-bug and ended up meeting each other in Beaune, both on their own wine-pilgrimage. Alex was born and raised in the area of Dresden and came to wine through architecture. Christoph was raised in Baden and a bottle of Burgundy was so compelling that he ended up just jumping on his motorcycle and heading west.

Over a period of nearly a decade, both garnered pretty serious Burgundian credentials, working at Comte Armand, Bernard van Berg, Leflaive, de Montille, Pierre Morey and Domaine de la Vougeraie. Alex, in fact, was the vineyard manager for de Montille until 2021.

How could he have worked for de Montille and be involved in winemaking in Baden? As it turns out, Burgndy is only about two-and-a-half hours due southwest from Baden y’all, just FYI.

Now, I do not want this to be yet another vague and salesy essay about how Baden can make Burgundian wines; at the same time, the similarity in geography and, in some cases, soil type should also not be ignored. In any event, in this case, the geographical proximity allowed Wasenhaus to exist, at least at the beginning.

As for the wines, the measured introduction would be something like: these are among the most talked-about wines in Germany and they deserve this status. Honestly, I’ve had few people taste these wines and not have an eyebrow raise or a jaw drop. They are not only that good, but they are that obviously good.

Similar to Enderle & Moll, the Wasenhaus Pinot Noirs show an uncommon lightness and clarity; a finesse that embarrasses most other German Pinot Noirs. While Enderle & Moll tends to present more structured, a bit more tense and wild, the Wasenhaus wines are ultra-fine, with a textural elegance that is second to none. If Enderle & Moll is punk rock; Wasenhaus is chamber music or jazz (?) – one isn’t better than the other, but they are very different.

While the Pinot Noirs are showstoppers, the Chardonnays compelling, the Weissburgunders, for me at least, are revelatory.

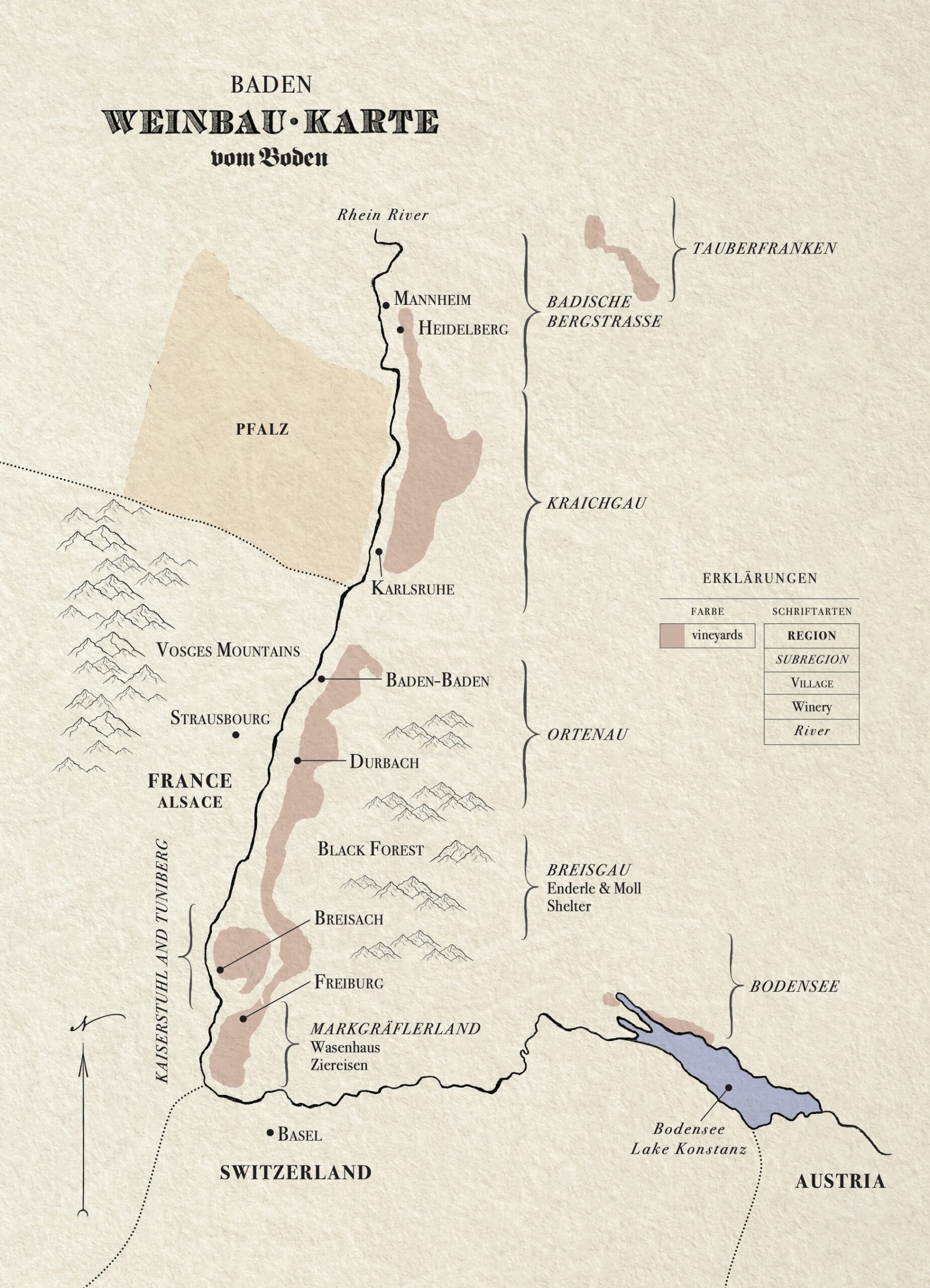

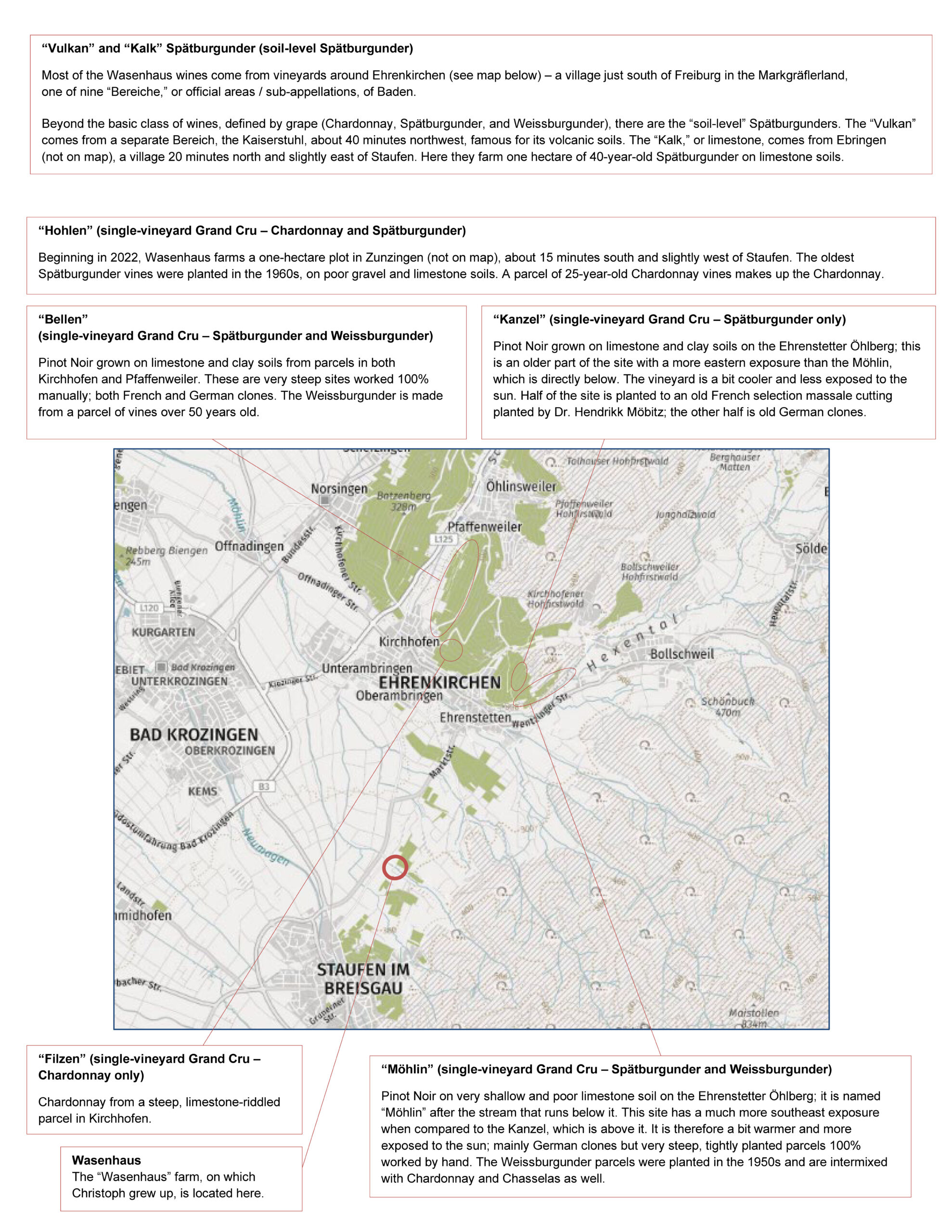

The focus at Wasenhaus (thus named after the farm that Christoph grew up at, focusing on horses and not wine) is old vines, old clones, and in general curious parcels that dot the landscape of southern Baden (the to the right is a general map of Baden; the map lower down in the right-hand column, illegible until you click it, gives you details of their holdings around Ehrenkirchen). Alex and Christoph seek out vineyards that have been ignored because they are too hard to work, because the yields are too low, or for whatever quirky reason. The great majority of their holdings come from near Ehrenstetten though they do have holdings in villages a touch north (Ebringen) and a touch south (Zunzingen). They also farm a few parcels in the Kaiserstuhl, an area maybe forty minutes north and west; all these grapes go into the “Vulkan” bottling.

But let us discuss the wines. As all the wines are bottled as “Landwein” the labels may not bear any village or vineyard names, thus they have to be a bit inventive here.

The basic hierarchy, though still dynamic, does seem to have found its place. As but a simple primer: There are the basic, estate-level wines, named after their varietal. We have a Chardonnay, a Spätburgunder, and a Weissburgunder. All of these wines, in general, come from younger-vine parcels, though depending on the vintage’s strengths or weaknesses, the exact parcels may vary.

Then we have to “soil-level” Spätburgunders; there are only two. There is the sole Kaiserstuhl offering, the “Vulkan” as mentioned above, boldly proclaiming its volcanic, Kaiserstuhl soils. Then there is the counterpoint, the “Kalk,” a limestone-soil Spätburgunder largely, though not exclusively, sourced from lovely, 40-year-old vines in Ebringen.

Next, we move on to the single-vineyard wines. First, there is the “Bellen,” sourced from vineyards between Kirchhofen and Pfaffenweiler (again, the map below to the right, illegible until you click it, will be of great service here). These are limestone soils and this is one of the finest wines they make, to my humble palate. There is both a Weissburgunder and a Spätburgunder. The “Filzen” vineyard produces but one Chardonnay; this is a steep, limestone-rich vineyard in Kirchhofen. “Hohlen” is a newer single-vineyard wine; the first vintage was 2022. This wine comes from a single-hectare parcel (roughly) in the village of Zunzingen, about fifteen minutes south and slightly west of Ehrenstetten. The oldest Spätburgunder vines here were planted in the 1960s; the Chardonnay is sourced from a parcel twenty-five years old. The “Kanzel,” a tiny site made famous (at least for some German wine dorks) by Henrik Möbitz, is now farmed by Wasenhaus; I believe the first vintage was 2020? This is a cool, limestone and clay parcel at the top of the Ehrenstetten Öhlberg – a site name they cannot use. So they call the wine what Möbitz called it: Kanzel. Finally, there is the “Möhlin,” one of their most impressive sites. Sitting below the “Kanzel” and winding its way into the valley, the “Möhlin” is also clay and limestone soils. This is a soulful vineyard, with tight rows planted on polls (the photograph of Christoph, below, is from the Möhlin). They make both a Spätburgunder and a Weissburgunder from the Möhlin. Both wines are majestic and enveloping; these are perhaps their most complete, most monumental wines.

The farming is organic with elements of biodynamics woven in, though they are certified in neither. The winemaking is low intervention. The white wines are all whole-cluster pressed with a basket press; the élevage is in neutral barrels of varying sizes. The reds are fermented in open-top vats and then aged in neutral barrels as well – they can use anywhere from no whole clusters to complete stems depending on the vintage. Only natural yeasts are used, and all wines are bottled unfined and unfiltered. Sulfur is used only at bottling and minimally.

They are currently farming around six hectares and purchasing fruit from about two extra hectares. If you’d like to be put on the mailing list to be alerted to when we receive any Wasenhaus wines, please email us at info at vomboden dot com.