“These are consistently among the top wines produced anywhere in the Mosel, made from painstakingly strict selections from prime steep vineyards planted with old un-grafted vines. Yet prices remain moderate… Savvy readers should plunge on these wines.”

– Mosel Fine Wine Review

At the turn of the 20th century, Traben-Trarbach was one of the wealthiest towns in the Mosel. It was the beating heart of the trade in what were largely considered the greatest wines in the world: Mosel Rieslings. I’ve read that this little village was the second largest commercial center for wine in western Europe, second only to Bordeaux. Much of the grand architecture of Traben-Trarbach was built during this period – stunning Jugendstil masterpieces (“Art Nouveau” in French). The Hotel Bellevue, which rests majestically along the Mosel, is perhaps the most iconic building of the village. In 2013, when these amazing humans decided to work with me instead of the better-known importers that were wisely courting them, we went here to celebrate. It feels like a lifetime ago.

In any event, this era informs much of the feel of Weiser-Künstler. Their beautiful labels take their cue from the Jugendstil designers of this age. They are a denial of the mechanical world’s obsession with harsh angles and straight lines; they lean into the organic world, the natural world. The theme of the owl comes from this aesthetic philosophy, though it’s also a sort of wordplay referring to Konstantin’s last name – Weiser – which might translate to “one who knows” in German. “Weisheit” is wisdom and the owl has since at least ancient Greece been a symbol of wisdom.

For all this, the font looks as if it’s right out of a Gustav Klimt poster.

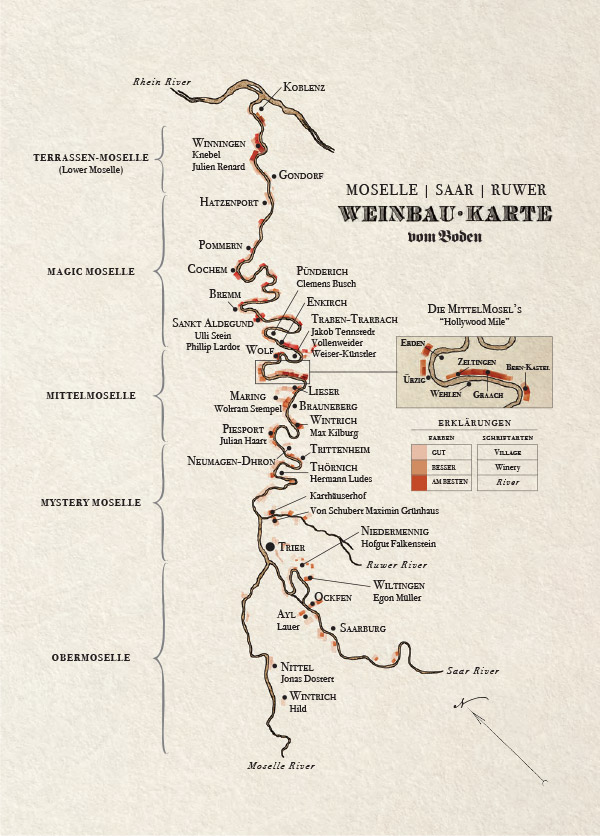

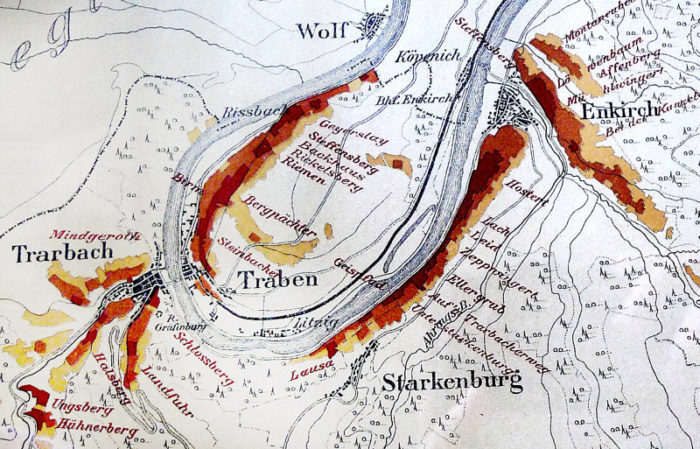

More importantly, however, the dawn of the 20th century was the height of fame for the vineyards that Weiser-Künstler now farm. The map of the Mosel from 1897 (see the “Wei-Kü Vineyard Tour” tab below) shows the three key vineyards of Weiser-Künstler (Ellergrub, Gaispfad and Steffensberg) all with “Grand Cru” status, though I think it’s a bit simplistic to say that this guarantees any current-day greatness. Plenty of the sites this map declares as “great” are dormant today and questionable regardless; other sites not even included are today acknowledged as phenomenal. Times change, ya know?

Still, this trio of vineyards is great. This is an awesome and formidable wall of vineyards that people far smarter than I have claimed as among the best in the Mosel.

The simple truth seems to be that in the post-war period, with its trend toward mechanization, these terraced, craggy and ornery vineyards fell in status; they were largely abandoned. They were simply too hard, too expensive to farm. Yet the fact that these vineyards fell into obscurity for this period isn’t entirely a bad thing. Because this area was so poor, because it was overlooked, the vineyards here have simply not seen the “modernization” that many sites in the Mosel have. This, in turn, means that these cliff-vineyards still have their jutting, ladder-like terraces and on these terraces, they have many, very old un-grafted vines – far, far older than most of the famous sites which were largely replanted with more modern clones through the 1960s, 1970s and beyond.

As but one example: The mighty Ellergrub has a preponderance of ungrafted vines well over 100 years old; the Gaispfad is younger with ungrafted vines only around 80 years old.

This is a place, literally, where roots run very deep; you can taste that profundity in the wines.

The husband-and-wife team of Konstantin Weiser and Alexandra Künstler (pictured above) are perhaps the ultimate winemaker’s winemakers.

I have never come across any estate, famous or not, that has expressed anything but awe for what these two do, which is, in short, the following: They farm organically (certified) in a very wet and humid place, in the steepest slopes where there can be no mechanization, receiving meager yields because they farm some of the oldest vines in the Mosel, including 80-100+ year-old, ungrafted vines. In a world of compromises, compromises that are easy and lazy and speak to our weakest selves, but also those that are necessary and painful and speak to the awkwardness of the human condition, Alexandra and Konstantin seem to make no compromises.

They do, in a way, what I suspect most wineries would want to do, in some crazy, distant, ideal world that does not exist. But Weiser-Künstler does it. And I have seen few people smile more.

This is a bit nuts to mention – in a wine estate profile on a website written by a confused agnostic – but they both feel to me like deeply spiritual people, deeply sensitive. They have a way of holding themselves that is so quiet and peaceful. Even when they are 100% engaged with you, one has the sense they are, at least in a way, somewhere else as well. It’s a welcoming energy; you want to be around them, but it is not a world of back-slaps and loud laughs. It is a calm.

And the wines seem to me, too, to have this aloofness.

Many of their bottlings remind me less of wine, in fact, and more of some wildly delicate distillates (with ABVs of 10% or less), or of very complex spring waters, or of teas? There is fruit present, especially in the Kabinetts and sweeter Prädikat wines, but even here it is often phenolic – not green apple, but green apple skin, not peach, but peach pith.

Their style is one of the most singular, most unique in the Mosel. These are wines of the earth in ways that are rarely presented so unadulterated.

I think these are perhaps the most cerebral wines in the vom Boden book. Because of this, because of their complexity and calm, but also because of supply-side challenges (they make just excruciatingly small quantities of wine), the estate remains curiously unknown and, at least to my mind, overlooked in the US.

One of the most compelling arguments, for me personally, that the universe might not have any meaning is that these wines are not worshipped. Purer, more humble and fairly priced expressions of one of the world’s oldest wine cultures simply do not exist. It’s true, a small minority fanatically collects these wines (I am one of these people), yet the larger audience seems to have no context or experience with them.

It’s not my job to explain any of this. These are not easy wines; they are I guess not for everyone. But for those open to quiet beauty, to thoughts and whispers and long silences brought into clarity, please try and find these wines. And then treasure them.

Finally, floating further downstream we come to the trio of Grand Crus that has made and solidified the reputation of Weiser-Künstler. First we come to the iron-rich Gaispfad (1:05 seconds), a uniform yet very steep rectangle of vines 80+ years old and largely ungrafted. Alexandra and Konstantin farm about 0.6ha in this site.

Finally, floating further downstream we come to the trio of Grand Crus that has made and solidified the reputation of Weiser-Künstler. First we come to the iron-rich Gaispfad (1:05 seconds), a uniform yet very steep rectangle of vines 80+ years old and largely ungrafted. Alexandra and Konstantin farm about 0.6ha in this site.