In Baden, there is only David or Goliath. Could it be that politics, of all things, is at the heart of Baden’s true challenges — today and historically?

For most of the last few centuries, Baden has been a complex tapestry of various empires, royal holdings, church states, random principalities, and other constructs the likes of which transcend our current language of sovereign self-rule. Warring factions of one type or another, and the chaos that this created, defined much of this region for many centuries.

It’s hard to focus on viticulture when everything is a battlefield.

Today, the political challenges still involve land, yet this time the battle revolves around vineyard land. The warring factions are the mega-sized cooperatives that own huge tracts of land and exert their overwhelming buying power to depress the prices of vineyard land and grapes. They push a wine culture based solely on low prices and the race to the bottom.

Pushing against this immense commercial force are the small growers, bottling their own wines and trying to bring a higher quality and a more focused identity to this place.

There is a reason that nearly any Baden estate you’ve heard of is on the smaller side; with some exceptions, there is almost no middle class here. In Baden, there is only David or Goliath. There is also a reason that many estates from this region bottle their Pinot Noirs with the word “Pinot Noir” on the label and not the German word “Spätburgunder.” They know the local, German-speaking market will not support them, dominated as it is by the cooperatives. Small growers in Baden seeking success, at least over the past few decades, have had to concentrate their efforts in the export market. Thus the more international terminology: “Pinot Noir.” We will return to this topic, later.

A suggestive, if slightly inane, way of thinking about Baden is as the Burgundy of Germany.

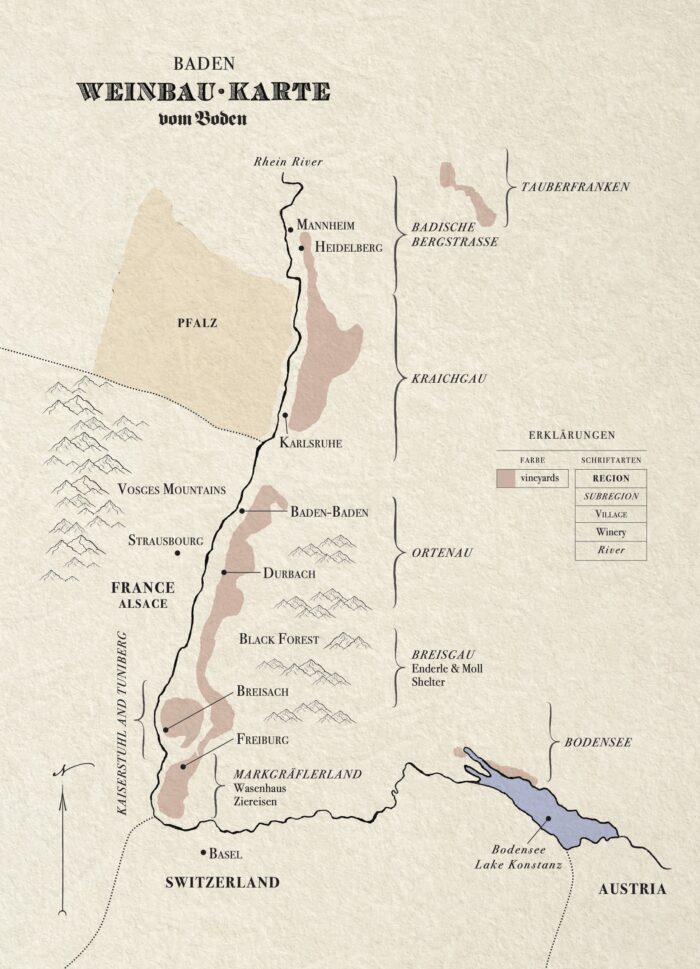

Certainly, this is ground zero for Pinot Noir — or was. Franz Keller and Bernard Huber put the place on the map in the late 1980s and early 1990s; current champions of the grape in Baden include Enderle & Moll, Dr. Heger, Salwey, Shelter, Wasenhaus, and Ziereisen.

Another way to think of Baden, perhaps useful for the Francophile: The Rhein River is the spine of a tall skinny book. The right page of this book is Baden; the left page of this book is Alsace. Baden and Alsace are in fact mirrors of each other, with the Vosges Mountains marking the western edge of Alsace and the Black Forest defining the eastern edge of Baden — the left edge and the right edge of our hypothetical book. National borders notwithstanding, both regions, Alsace and Baden, are simply the fertile basin formed by the Rhein River as it heads north toward Mainz, where it makes its famous westward turn, creating the Rheingau.

Some say that Charlemagne’s great-grandson had vines from Burgundy planted here in the 9th century, suggesting the arrival of Pinot Noir in Germany, though we don’t know for sure. Certainly by the 14th century there are reports of various monasteries planting Pinot Noir, including one in Malterdingen, where Shelter is. We do know that by the late 18th century, in the region near Durbach (labeled on the map), the first single-vineyard Riesling was planted in Baden below the castle of Klingelberg, hence the name that people in the area still call Riesling: Klingelberger.

Yet what sort of wine culture really existed here over the centuries we hardly know — very little or none of this wine made it to markets much beyond Baden itself. Hugh R. Rudd, writing in 1935, makes no mention of the region at all. Schoonmaker, writing in 1956, dedicates only a few pages to Baden, it being one of four regions he covers in a sad chapter entitled “The Lesser Districts,” which also includes the Ahr, the Bodensee, and Württemberg.

But let us step back and take a wide-angle view of this place.

The fact that Baden is a large winemaking region — around 16,000 hectares — isn’t the most interesting or relevant fact about it. The most important thing to consider when considering Baden is its size in relationship to its immense span, north to south. With two exceptions, the outline of Baden looks like a long, bony finger, beginning just north of Basel (in Switzerland, y’all) and extending northward, all the way to near Mannheim.

Numerous wine writers have noted that Baden covers two full degrees of latitude, from 47.5 degrees up to 49.5 degrees.

For those of you not intimately familiar with degrees of latitude, each degree represents approximately 70 miles. So in total, we are talking a distance of some 140 miles, north to south, roughly the distance from New York City to Wilmington, Delaware, or from Los Angeles down to San Diego, California.

In other words, Baden is a long damn tract of land that is, in most places, only a couple of miles wide, extending from the Rhein River (the border between Germany and France, as discussed) up into the Black Forest. As you can imagine, the difference from north to south is serious. Currently this span is divided into nine regions, or Bereich, by the German wine authorities. From north to south, these are Tauberfranken, Badische Bergstrasse, Kraichgau, Ortenau, Breisgau, Kaiserstuhl, Tuniberg, Markgräflerland, and the Bodensee (Lake Konstanz), just so you know. I won’t really go into these regions in any more depth because I’m not convinced they have unique identities, quite yet, other than perhaps the Kaiserstuhl, a volcanic outcropping south and west of Breisgau and north and west of the Markgräflerland.

The larger and more obvious truth is that within this immense distance south to north, we have multitudes upon multitudes of micro- climates. The growers are working through this riddle as we speak.

It’s funny that what Stephen Brook wrote in his 2003 book, provocatively titled The Wines of Germany, remains true nearly two decades later and speaks, exactly, to what I just mentioned: “Baden wines and Baden wine marketing are, in short, a bit of a mess…. Individualist growers simply go their own way and trust in the quality of their wines to secure a share of the market…. It seems probable that the stern demands of the market will eventually impose some discipline on a fairly chaotic region. Until that happens, the search for ever better quality rests firmly in the hands of independent growers.”

So far, the stern demands of the market have not been strong enough to shape meaningful regional identities. I mean, can you name two ways the Ortenau differs from the Markgräflerland?

Quality still rests firmly in the hands of independent growers, though the market of late has been quick to identify quality and to reward it.

The rare wines of Henrik Möbitz have become quite pricey, if you can find them. Enderle & Moll quickly sells out; Wasenhaus has gone cult. Importers that long focused on French wines and never looked beyond the Rhein now see the success, the opportunity, and, yes, the money to be made in this country they’ve long ignored.

For nearly all of them, Baden is the gateway to Germany. For all its regional complexities, Baden grows very little Riesling and so avoids the complex terms that come with Riesling. There is no “Feinherb” or “Spätlese Trocken” to deal with.

There is an abundance of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Yup, Baden is a land, as we’ve stated, made for export. Prepare for Baden.

In the battle of the cooperatives versus the small growers, the most recent news I’ve gathered from the field is that the small-grower culture here is thriving. So things seem to be leaning in the right direction, at least as far as quality is concerned. The work for these growers for the next few decades will be decoding the microclimates of this complex place and articulating its various identities. I look forward to all of us knowing two ways the Ortenau differs from the Markgräflerland. Maybe even three.