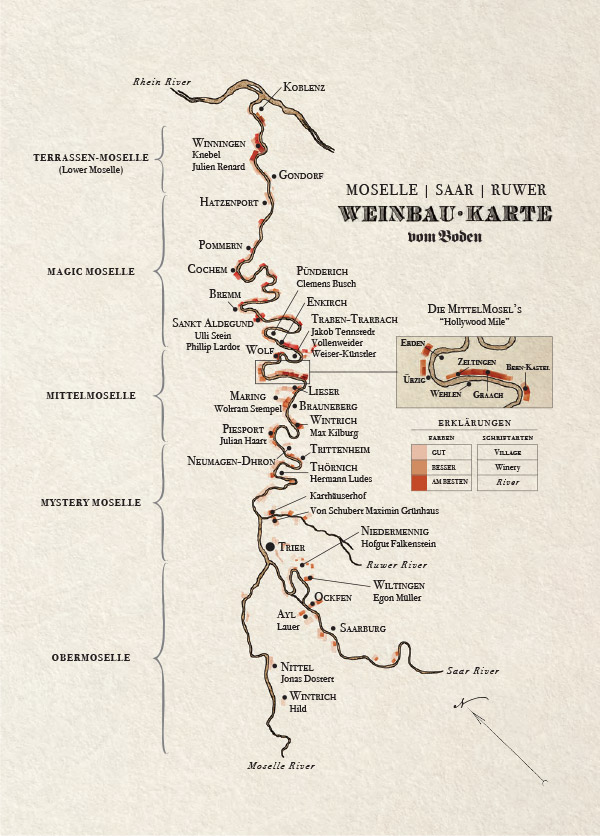

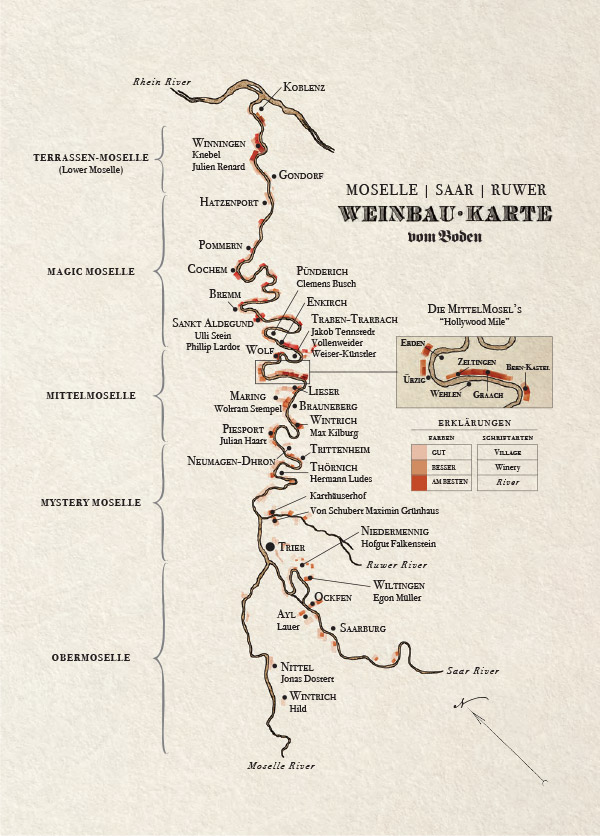

Officially, the Mosel has three official sections: the Obermosel (Upper Moselle), Mittelmosel (Middle Moselle), and Lower Moselle, sometimes called the Terrassen-Moselle. While the Obermosel is quite clearly defined – it is the part of the Moselle that runs from the border of France at the south until Trier, at the north – the Mittelmosel has different boundaries, depending on who you talk to. Some say it includes everything from Trier downstream until Erden, or until Traben-Trarbach; the most constricted reading I’ve seen says the Mittelmosel consists only of the area from Piesport until Erden. In short: It’s unclear. But more, any tripartite division seems to me to either ignore the region from Trier downstream to Piesport, and/or blend what is a very specific and singular landscape around Winnigen (the Terrassen-Mosel) with a huge stretch of the Mosel that is nearly ignored by most national (and domestic German?) press: The part from say Zell and Sankt Aldegund down to Gondorf. This is nearly a third of the Mosel, roughly, when you look at the map to the right.

I have a proposal: Divide the Moselle into the following five sections, running from the southern border of Germany near Luxembourg all the way to Koblenz, where the Moselle finally offers itself to the Rhine. Keep in mind, two of the sections you’ll see detailed on our map to the left — the “Mystery Moselle” and the “Magic Moselle” — I have created. I think these subdivisions are useful and add insight into the Moselle, but they are my concoctions.

I have a proposal: Divide the Moselle into the following five sections, running from the southern border of Germany near Luxembourg all the way to Koblenz, where the Moselle finally offers itself to the Rhine. Keep in mind, two of the sections you’ll see detailed on our map to the left — the “Mystery Moselle” and the “Magic Moselle” — I have created. I think these subdivisions are useful and add insight into the Moselle, but they are my concoctions.

First, there is the Obermosel.

This is an official region: the limestone world of Elbling, an area completely overlooked (at least by the fine-wine cognoscenti) until only a decade or so ago. This place represents the easternmost part, the conclusion, really, of the Paris Basin, a huge swath of Kimmeridgian limestone that runs from the cliffs of Dover through France and slams into the Rhenish Slate Massif. Drive 15 minutes from the Obermosel into, say, the Saar, and you have crossed from the Paris Basin into the Rhenish Slate Massif. It’s a ho-hum drive through gentle rolling hills and quiet agricultural villages, yet you cross from one geological world into another. It’s wild.

Next, beginning at Trier and running through a rather unknown collection of villages, with a few renowned diamonds, we have what I call the Mystery Moselle.

Why the name? Because to a large extent this section remains a mystery to me and, I presume, to the American wine lover at large. It’s also a mystery to me why it’s a mystery. What the hell is happening here, and why don’t we know more? The village names of this section are often unfamiliar to even serious students of German wine: Longuich, Mehring, Pölich, Detzem, Thörnich, Köwerich, Klüsserath, Leiwen, Trittenheim, and finally Neumagen and Dhron. There are some profound sites here, a few stars and some rising stars, but for the most part, people don’t pay that much attention to this section. A few sites and estates (Hermann Ludes, A.J. Adam) make me think we really should be.

Next, the big dawgs line up.

The famous Mittelmosel runs, I’d say, from Piesport all the way down to Enkirch, though people will debate where exactly it begins and/or ends. The Mittelmosel is what 90% of German wine lovers talk about when they talk about the Moselle.

Every famous vineyard I quoted at the beginning of this chapter — Doctor, Goldtröpfchen, Himmelreich, Sonnenuhr, Würzgarten — is in this part of the Moselle. All of them except the Goldtröpfchen are nestled in what I call the “Hollywood Mile” of the Mittelmosel, beginning at Bernkastel and running through Graach, Wehlen, Zeltingen and ending at Ürzig and Erden. See the detail on the map. It’s incredible what a tiny part of the Moselle this section is.

Now, while most people would jump right into the Lower Moselle, or Terrassen-Mosel, I don’t think this reflects the actual landscape.

I’ll add one more section, and an important one at that: the “Magic Moselle.”

This section runs from Burg and Reil to Clemens Busch’s Pünderich, then around the big 180-degree turn to Briedel, Zell, Merl, Ulli Stein’s Bullay, Alf and St. Aldegund, to Bremm with its unrealistically steep Calmont, Valwig, Cochem with its famous castle, all the way down to Kobern. You’ve likely never heard of most of these names, so what’s magic about this place?

The magic is the old vines, the genetic cultural heritage that is here. This genetic cultural heritage is an important part of the Moselle at large. Tiny islands of ungrafted vines 50 to 100 years old and older dot the entire length of the Moselle. Growers here will nonchalantly speak of parcels planted near the turn of the (last) century; they raise their eyebrows and laugh gently to themselves when they see “Vieilles Vignes” declared at 30 or 40 years. In the Moselle, these are adolescents hardly even worth considering; they go into the most basic cuvées.

Yet there is more at stake here than the growers’ bragging rights. If 99% of the vines of Europe are on American rootstock, the Moselle is one of the few places where this pre-phylloxera heritage remains, somewhat unscathed. Can you taste the difference? Certainly the depth and complexity of old vines is unquestionable; whether the ungrafted detail is discernible I can’t honestly say. But for me the true importance of these old ungrafted vines rests not in any specific quality of the wines they produce, in the same way the importance of the Parthenon rests not in the specific quality of the marble or the incredible sophistication of the design.

What is important is the history, our united human history, here and tangible for our present and our future. This is one of the greatest, rarest, and least-spoken-of treasures of the Moselle. To me it is perhaps the most important.

And while these ungrafted vines are not exclusive to the Magic Moselle, as stated, it is my sense that they are more present here than anywhere else in the Moselle. Why? In a way, because of obscurity, indifference, poverty.

And while these ungrafted vines are not exclusive to the Magic Moselle, as stated, it is my sense that they are more present here than anywhere else in the Moselle. Why? In a way, because of obscurity, indifference, poverty.

The Flübereinigung, or the renovation and reorganization of the vineyards in the postwar period, smoothed out many of the slopes of the Mittelmosel, like an iron being pressed to a wrinkled shirt.

But it rarely made an appearance in the Magic Moselle. Most of the villages here were too poor to help subsidize this expensive undertaking. Just as important, the names of the villages and vineyards weren’t important enough brands to bother making them more efficient and economically viable. Who cared?

The Flübereinigung in most cases involved ripping out large sections of vines to make room for small roads and to reorganize the plots in a way that made them easier to farm mechanically. This is not inherently a bad thing: In many cases the Flübereinigung helped make many of the sites not just more economical but actually sustainable. This process undoubtedly saved many parts of the Moselle. At the same time, one must acknowledge that the process also eliminated at least parts of a cultural heritage, of a genetic heritage, that you can still find in the Magic Moselle.

For me, the Magic Moselle looks more like the Mittelmosel than the Terrassen-Moselle. The general aesthetic is a patchwork quilt not unlike Burgundy in appearance, yet at a more severe incline. However, in the Magic Moselle these clean lines are disrupted here and there by jutting, sometimes awkward, oftentimes spectacular terraces, rising up like small angular monuments to an earlier version of the Moselle, which is in fact exactly what they are. These are the terraces that were not destroyed as a part of Flübereinigung.

The Magic Moselle is the least famous part of this entire river. Even the Mystery Moselle has a few headliners: the Trittenheimer Apotheke, the Thörnicher Ritsch, the Dhroner Hofberg. While German-wine dorks will recognize Clemens Busch’s Marienburg or Ulli Stein’s Palmberg- Terrassen, or perhaps the historical fame of Zell’s Schwarze Katz, there are few sites of any repute for the average wine enthusiast.

But there are many old vines here, many of them ungrafted. And there is a generation coming to the Moselle to mine these riches, to save these vineyards. It should be our duty to support them.

Finally, just past Kobern, the Moselle bends a little — a final whip of creative energy — and the true Lower or Terrassen-Moselle begins and then abruptly ends. Yes, for me the only village that truly belongs in the Terrassen-Moselle is Winningen, with its Uhlen and Röttgen vineyards. For me the Terrassen-Moselle is a very short stretch of truly mind-boggling fortress-vineyards, more slate walls than vines. This is a distinct part of the Moselle, unlike anything else.

Curiously, while the Terrassen-Moselle represents the northernmost point of the Moselle, it is often considered the warmest part. The steep vineyards, with their massive and multitudinous walls, soak up the sun. These are among the most broad and powerful wines of the Moselle. Based on my recent time spent in Winningen, Pinot Noir seems on the ascendance here as well.

When I talk about the Moselle, I use all five of these regions. If it’s useful to you, please feel free to use them as well. Just keep in mind that two of these regions are my personal creations. I think both the Mystery Moselle and the Magic Moselle are meaningful and reflective of what the Moselle really is — they add to the discussion — but if you have dinner with the famous British wine scholar Hugh Johnson and cite the “Magic Moselle,” he will look at you like you’re an alien and question your taste in Claret, your ascot, and everything else.

You can blame me.