For the serious German-wine fan, the Nahe is unquestionably elite. What we perhaps don’t quite realize is that it’s also something of a developing story.

I think the single wildest thing about the Nahe is the explosive, meteoric rise of the place, from essentially a B-side of the Rheingau, with little real identity of its own, to one of the most prized terroirs in Germany.

I think the single wildest thing about the Nahe is the explosive, meteoric rise of the place, from essentially a B-side of the Rheingau, with little real identity of its own, to one of the most prized terroirs in Germany.

In 2003, Stephen Brook wrote the following in his provocatively titled book, The Wines of Germany: “If the Nahe region, which was established administratively in 1930, seems to lack identity, that is surely because it does lack identity.” Brook’s book is in general very well researched and truly excellent, yet it does not even mention Schäfer-Fröhlich or their home village of Bockenau.

Four years later, Braatz, Sauter, and Swoboda write in their 2007 Wine Atlas of Germany: “Indeed, in spite of the good reputation of the Rieslings from the emergent estates of Helmut Dönnhoff, Hans Crusius, and Schlossgut Diel, very few German or foreign customers know that these wines come from the Nahe…. The enormous potential of the entire region and the marked variety of its soils have not been well exploited or promoted.”

Schlossgut Diel and Dönnhoff as emergent estates? No customers know that the wines come from the Nahe? Huh? This was written in 2007, folks.

Then, only 12 years later, Anne Krebiehl, in her 2019 book, provocatively titled The Wines of Germany, gave the following title to her chapter on the Nahe: “Triumph at Last.”

Yes, the Nahe has gone from not even a contender to a champion, from a geographic backwater of sorts to the chicest of real estate, in only 16 years. And it’s all taken place right under our noses.

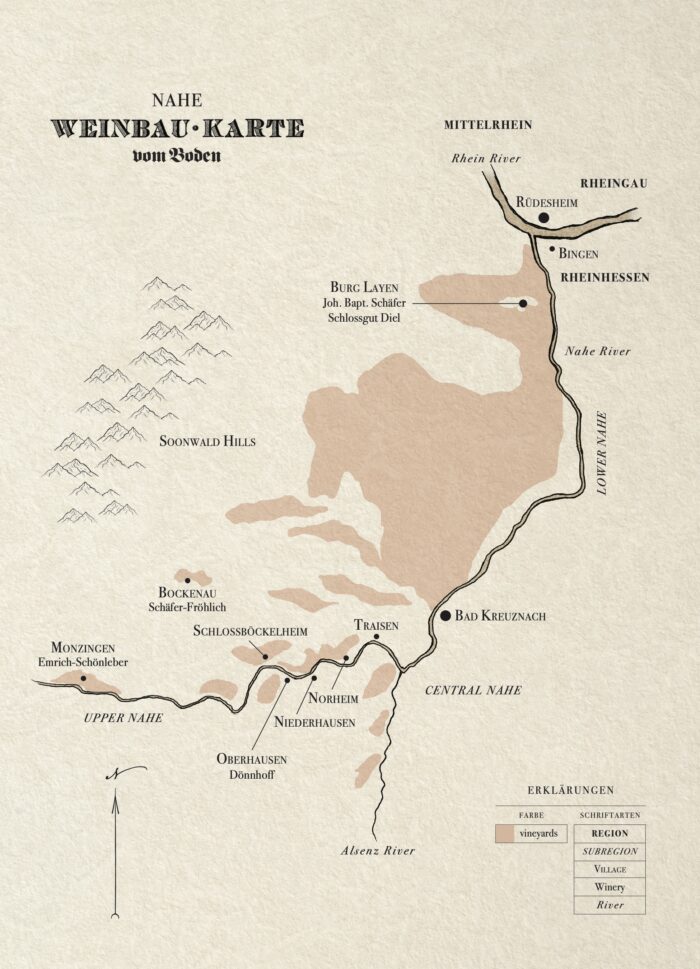

Consider that the stories of the three most famous estates in the Nahe — Dönnhoff, Emrich-Schönleber and Schäfer-Fröhlich — largely began in the 1990s. The Nahe, as we know it today, really only began in the early 2000s.

Yet a decade later, by the vintage 2010, the top producers were already legends. That’s fast.

How do we account for the meteoric rise of this region?

This is another long story, but I think the summary would be something like: It was a most sublime coordination of the universe, which with beatific wisdom paired a small group of wildly talented and ambitious growers with a very specific place that, thanks at least in part to climate change, was coming into a hallowed sweet spot right as they were beginning their careers.

You should check out the Emrich-Schönleber movie we made (it’s only around 12 minutes long). In it, Werner Schönleber, a giant in the world of German wine, said the following about the Nahe: “I think we can say now that the best talents have the best terroirs.”

The rest is history, even if it is a relatively recent history.

Now, with all that covered, trying to articulate the exact nature of the wines of the Nahe, well, this is a wine writer’s sport, going back a century and probably more. It’s often said that the Rieslings of the Nahe can have something of the soaring agility, the slim compact- ness — the finesse — of the Mosel. Frank Schoonmaker in his 1956 tome, brilliantly and properly titled The Wines of Germany, disagrees, writing: “Because of the fact that the Valley of the Nahe lies between that of the Moselle and the Rhine Valley proper, some writers have chosen to say that the wines, too, are midway between the Moselles and Rhines in character. This seems to me a poor way to describe them: their qualities are their own; the best of them are grown on red sandstone soil very different from the slate of the Moselle, and their bouquet, however admirable, is not a Moselle bouquet by any means. It is, as a matter of fact, more like that of a good Niersteiner” — which is to say, more like the wines of the Rheinhessen’s Roter Hang.

That said, with deference to Schoonmaker, I agree with a line of thinking that rather surprised me the first time I read it. It was articulated by Hugh R. Rudd in his 1935 book Hocks & Moselles and he dared to compare the Nahe not to the Moselle, but to the Saar.

Insert head-exploding emoji here. The Nahe and the Saar? Jawohl!

I think this comparison is deeply true and worth keeping in mind, especially in the upper parts of the Nahe, where the wines can most certainly have a certain steeliness (think Emrich-Schönleber and Schäfer-Fröhlich). And, again with respect to Schoonmaker, there is plenty of slate in these parts. Krebiehl continues this line of thinking and includes a snazzy piece of writing in her 2019 book that I very much enjoyed: “Nahe Rieslings are taut, expressive, sometimes marginal but always slender. There are certain parallels to the Saar where thrill, clarity, focus and poise is concerned… [The Nahe] does not make wine for beginners — there is a steely edge to the best of them; an utter, uncompromising purity that wows true Riesling lovers.”

And when you consider the Saar comparison, think not only of the style, but also of the essential architecture.

In other words, Nahe wines, if sometimes steely and incomprehensible in youth, age very well. For something to remain poised and fresh 10 years after bottling, well, it needs to have a lot of coiled-up energy to begin with. Some of the absolute greatest aged dry Rieslings I’ve ever had have been from the Nahe — just saying.

Now, if the upper reaches of the Nahe are Saar-like, the Rieslings of the central and lower Nahe can have something of the depth and power of the Rheinhessen or Pfalz, though often in a more focused form. Numerous authors mention a certain “earthiness” with the Rieslings of the lower Nahe, and I have to say I agree. Perhaps this is what Schoonmaker means to reference with his comparison of the Nahe to the Rheinhessen’s Roter Hang?

While the Rieslings are the obvious stars in the Nahe, the full flex of this region is still developing. Nahe Weissburgunders (Pinot Blancs), Grauburgunders (Pinot Gris), and even the Müller-Thurgau (often called Rivaner) can have a thrilling force, a nervy backbone here. One can find Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc and all the “sophisticated” varieties, though I can’t say I’ve had many that seem truly distinctive. A few growers are even working with Pinot Noir, which shows tremendous potential here too.

On my Nahe wish list? An epic Silvaner — I shiver at the thought of a Nahe live-wire Silvaner. I’d like to just throw that out into the universe. Frank Schönleber? Tim Fröhlich? Kannst Du mich hören?