The reputation (or lack thereof) of the Obermosel seems to me the unlucky result of a rather spectacular collision of history, geography and geopolitics.

That’s a weighty sentence – let me explain.

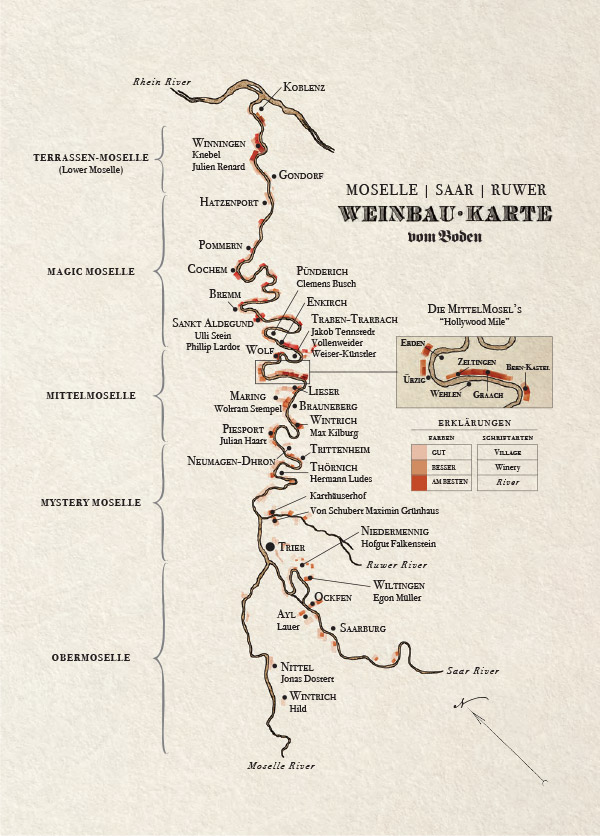

The Obermosel, or “upper Mosel,” is the region that begins where the Mosel crosses from France into Germany and then runs all the way until the river passes Trier. In the map to the right, you’ll see the “Obermosel” is the bottom-most bracket. For this stretch, the Mosel defines the border between Luxembourg (on the west) and Germany (on the east). From the border with France, all the way up to Trier, the distance is roughly 27 miles; it’ll take you around 40 minutes by car.

So, now that you know where the Obermosel is, the question remains: What is the Obermosel, really?

It is a rather quiet area, dappled with cozy little villages. While it is less dramatic than the cliff-vineyards of the Mosel at large, there is a domestic softness here, a stillness that feels fresh. (See the photograph below of the Obermosel valley.)

And what, exactly, is here? That answer is easy: Elbling.

Elbling is one of the oldest European grapes we know of likely brought to the Mosel region and planted by the Romans some two-thousand years ago. While at one time there were probably thousands of hectares of Elbling planted, today, in the entirety of Germany, there are less than 600 hectares.

For comparison, there are over 400 hectares of Riesling planted in the village of Piesport alone.

Let’s start with some history, though we can jump ahead from Roman times some 1,800 years, to 1787 and the famous Rieslingsedikt, the official decree declaring that Riesling alone should be the grape of the Mosel. This is the oft-quoted, history-making declaration by the Archbishop Elector of Trier that shaped the Mosel as we know it today – the Mosel as ground zero for Riesling.

The Obermosel was left out of the famous Rieslingsedikt simply because, at the time, it was a part of the Duchy of Luxembourg and, well, out of the control of the Archbishop Elector and his Riesling fetish (god bless him).

Thus we have a scant few hectares of Elbling in the Obermosel, simultaneously saved from, and committed to, oblivion.

This reminds me of a funny thing Matthias “Matz” Hild, one of our beloved Obermosel producers, once said to me: “We have the oldest cultivated grape in Germany! We have the wine the Romans drank! We have Kimmeridgian soil! We have only one big problem: No one knows what the **** Elbling is.”

For my own part, I had been traveling to the Mosel on wine trips since 2007 and I had never even heard of the Obermosel. It wasn’t until maybe six years later, when I started vom Boden and began driving, with some regularity, from the Mosel to my wife’s family in Strasbourg, that I began to wonder about this region.

“What are all these vineyards?” a youngish Stephen thought to himself driving due south from Trier. On my left, Germany and these little villages I didn’t even know the names of; on my right, Luxembourg and its moneyed suburbs.

As much as this tiny, forgotten region is absolutely a part of the world-famous winemaking region we call the Mosel (just look at the label of any wine from here, there you see it, “Mosel”), just as obviously, it is not in the least bit a part of it, not in terms of soil, grape(s), history, culture or, importantly, recognition.

First, the soil: The Obermosel is a Mosel awash in limestone. Put a different way: there’s no damn slate in the Obermosel. The limestone here is, in fact, that same limestone that informs parts of Chablis, Champagne and Sancerre. This tiny region marks the end of the Paris Basin, this humongous geological entity that, directly east of the Obermosel, slams into the Rhenish Slate Massif – that big ole chunk of slate that defines the Mosel.

It’s wild: The Obermosel is only about thirteen miles from Riesling’s most famous hillside, Egon Müller’s Scharzhofberg. It’s a fifteen-minute drive, passing through ho-hum villages and sleepy towns – yet during this drive we cross into a different geological world.

The Obermosel and the Saar specifically are so close, and yet there is no Riesling here in the Obermosel. Instead, as stated, we have the scrappy, joyful, indigenous, old-timer Elbling.

Let’s spend a moment discussing Elbling because in this area, as I’ve come to learn, Elbling is something of a religion. It’s a culture, a regional dialect that is spoken through this wine of rigorous purity, of joyous simplicity, of toothsome acidity.

Even at its best, Elbling is not a grape of “greatness” as much as it is a grape of refreshment and honesty and conviviality. The comparisons are plenty, though none of them are quite right.

If Riesling is Pinot Noir, then Elbling is Gamay. If Riesling is Sauvignon Blanc, then Elbling is Muscadet. You get the idea.

The joy of Elbling is its raucous acidity, the vigor and energy, the fact that it is so low in alcohol you could probably drink a bottle and still operate heavy machinery. (My lawyer here reminds me to insert that this is a joke; please do not operate heavy machinery while drinking Elbling.)

Our other Obermosel producer, Jonas Dostert, speaks about growing Elbilng in this region in a great interview published in the wine magazine B.Y.O.B.: “It’s difficult to handle, especially when you want to get it ripe. Even reaching just 10.5% alcohol is hard… What I like, though, is that it’s not famous… I think it’s really important to work with something that truly belongs to the area, something unique.” (B.Y.O.B. magazine, episode 1.2)

Until a few years ago, if anyone ever mentioned the Obermosel in your presence (an unlikely scenario even for the well-versed U.S. wine dork) it was likely a mildly derogatory remark, made in passing and without any real detail.

Similarly, for the lauded Riesling winegrowers of the middle and lower Mosel, the Obermosel isn’t on their radar any more than, say, Albuquerque, New Mexico is. If they’ve heard of Elbling at all, it’s a cheap grocery market kinda wine, likely sold as “white wine” and on the shelf for a Euro or two. Saying it’s not “fine wine” would be a most delicate way of putting it.

Maybe this is changing, slightly? Jonas Dostert, mentioned above, is friends with young growers in the Mosel and Rheinhessen. (Jonas is pictured to the right, in the center with his baseball hat on backwards. From left to right, one also sees Moritz Kissinger, Julien Renard, and Carsten Saalwächter.)

Maybe this is changing, slightly? Jonas Dostert, mentioned above, is friends with young growers in the Mosel and Rheinhessen. (Jonas is pictured to the right, in the center with his baseball hat on backwards. From left to right, one also sees Moritz Kissinger, Julien Renard, and Carsten Saalwächter.)

Yet Jonas’ reputation outside of the Obermosel is the exception, not the rule.

Truth be told, some of the Obermosel’s lackluster reputation is deserved: The Obermosel has had a long tradition of selling grapes by the truckload (literally) to cooperatives interested in high yields irrespective of quality. Some of this is explained by the deeper history and geography.

For our purposes, we can likely start in the late 19th century. This time period (1870 to the beginning of World War I) was a good time for German wine – a heyday of sorts. At the time, bizarrely enough, the tiny Protestant enclave of Traben-Trarbach on the Mosel River (also the current-day village of Vollenweider, Weiser-Künstler, and Jakob Tennstedt) was the second-leading commercial center for wine in western Europe, bettered only by Bordeaux. If Bordeaux did red wine, then the Mosel was the unrivaled region for world class white wine, period.

But the boom here was for more than what would have been mostly dry, still Riesling. Throughout the entire region, though likely centered in the Saar and the Obermosel, another industry boomed: sparkling wine. As Per Linder writes in his article entitled A Brief History of the Upper Mosel: “If the French invented Crémant, it was the Germans that succeeded to make a business out of it. Already in the first half of the 19th century, many German families emigrated to the Reims area, including the Krugs, the Bollingers, the Heidsecks and the Mumms.”

But many more families stayed behind and made sparkling wine in the Mosel. It is here where our friend Elbling and the Obermosel likely first makes its economic power felt. Per Linder writes that in 1850 there were about 50 sparkling wine production facilities producing roughly 1.2 million bottles a year. By 1903 there were over 100 producers making nearly 11 million bottles.

And already, the producers here in the Obermosel found themselves at a strategic disadvantage to the producers further downstream. The cause? Geography. They simply had to travel longer distances and had a harder time marketing their wares to the Riesling-centric commercial centers hours away. One solution to this? Focus more on quantity. And thus a bad habit began.

Still, from an economic standpoint, these were good times. While Elbling likely had little identity beyond the villages of the Obermosel, the market for good basic dry wines and for sparkling “Moselle” and, very likely, sparkling Moselle sold as Champagne, was good.

And yet, disasters, both self-imposed and not, were soon to destroy much of this region.

Beginning in the 1870s, phylloxera began to creep northward, coming up through the Lorraine and into both Luxembourg and the Obermosel. Then, of course, from 1914 through 1945 the area was devastated by two world wars. While it’s clear that viticulture survived here, it’s safe to assume it neither thrived nor developed significantly.

Matz Hild (pictured above) was the fourth of five children; he was born in 1957. Matz remembers growing up in this place and while no one was rich, there was a healthy market for these ultra-light wines. He never wanted for anything, was how he put it to me.

As the wine world became more and more of a global institution, the prices of grapes began to decline. The late 1970s and early 1980s were not a good time in the Obermosel. At about this time, Matz’s father founded the “Association of Friends of Elbling Wines.” If you’ve heard of a better name for an organization, please tell me. Who wants T-shirts?

Anyway, this was the beginning of a focus on the identity of the Obermosel, a focus on its past and cultural heritage.

The Hilds were in a unique position to lead this movement; there were, in fact, few estates that bottled and sold their own wines. Yet the Hilds had begun doing this at some point in the 1950s.

Matz took over the family estate in 1982. He has navigated treacherous waters. The Hilds make lovely, crispy Elblings. On my first trips to the Obermosel, many years ago at this point, the wines were unquestionably above anything else I had tasted from here: sharp, mineral, salty, honest.

Matz likes some bite; acid is a very real part of this landscape (remember the history of sparkling wine?). Matz told me at one point that in the 1980s, that if an Elbling clocked in with less then eight-and-a-half grams acid, he’d wonder if it was Elbling at all. Which is sorta like wondering if the music isn’t loud enough because your ears aren’t bleeding.

Yet for all the well-priced, honest wine they make, the Hilds are also engaged in cultural preservation. Look at the photograph below; these are Matz’s sisters, photographed in the 1960s, in front of a wall of terraced vineyards. I’ve sat on that very porch, exactly where those girls are. What you see now is a forest; the terraces have gone fallow… almost.

Despite the financial absurdity of it, the family farms the last remaining terraced vineyards of Elbling – I don’t think both of the terraced vineyards, taken together, total even one hectare. The rare juice from these old vines goes into a bottling called “Zehnkomanull,” meaning ten-comma-zero, because it rarely ferments to over ten degrees alcohol, even bone dry.

To me this wine is a semi-sacred voice from the past; a semi-sacred bottle that sits on the $20 shelf.

Hild was the first estate we started working with in the Obermosel. At the time, I had the suspicion that importing Elbling would bankrupt me, that in a slew of bad ideas (like starting a German wine importing company) this was the thing that would push me over the edge.

As it turned out, the bracing, refreshing, and honest Elblings of the Hilds did really well. People respond to authenticity – especially in this world of unending, digital, algorithmic bullshit.

In 2019, right before the world would go into lockdown, John and I heard of another small grower in the Obermosel. He hadn’t even started selling his wines. When the history book of the Obermosel is written, I want it noted that John and I were the first people to taste in the cellar with the young grower named Jonas Dostert.

Based in Nittel, Jonas was, to some extent, the physical incarnation of a dream I had had years earlier. I mean, here we have a very cold climate, Kimmeridgian soils – limestone! – and a unique culture of Elbling, but also the Burgunders (Weissburgunder, Grauburgunder), and Chardonnay and Pinot Noir beginning to make real inroads. It seemed to me inevitable that some sort of very impactful, serious culture of wine would develop here.

Dostert has had incredible success for a grower from the Obermosel. His wines are perhaps the first that are being taken very seriously by a critical establishment that has forever ignored the Obermosel. But the going has not been easy, and for the next few years (decades?) there will be a lot of explaining to do about the Obermosel.

Hopefully now you can help us spread the good word?

Much – but not all – of this writing was taken from our Journal (008) on the Obermosel, provocatively titled: “The Obermosel: no story is told, until someone tells it.”

Click here to go even further down this rabbit hole.