I don’t think we really understand what the Pfalz is.

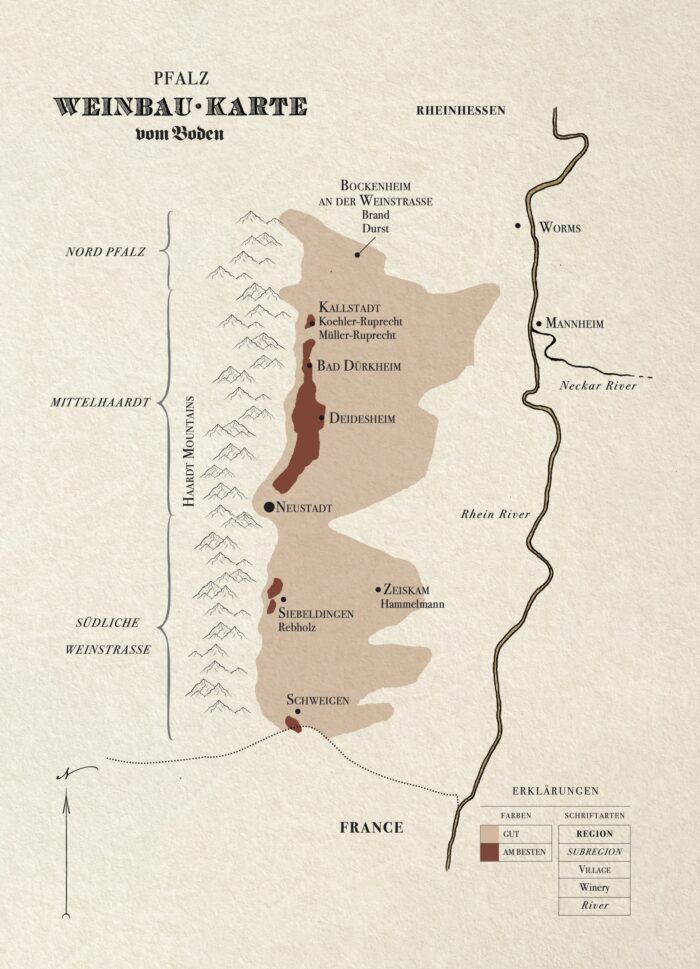

The Pfalz is a tract of land running north from Alsace, along the western side of the Rhein, ending at the Rheinhessen around Worms — a total length of about 80 kilometers (50 miles). In a way, the Pfalz is a continuation of Alsace, with the most famous vineyards tucked into the east-facing slopes of the Vosges Mountains, which in Germany are called the Haardt Mountains. The southernmost town in the Pfalz, Schweigen, has vineyards that actually extend a little bit into France.

From this southern tip of the Pfalz, one drives about 45 kilometers — a bit over a half-hour — to get to the center of the Pfalz, the Mittelhaardt, one of the most famous wine areas in Germany. While serious German-wine fans might recognize some of the village names (Forst, Deidesheim, Königsbach) or some of the vineyard names (Pechstein, Ungeheuer, Kirchenstück, Hohenmorgen, Idig), the U.S. market hasn’t really understood the Pfalz in a long time. Not only are the famous Grand Crus of the Pfalz not as famous here as they are there, but I don’t think we even really understand what the Pfalz is to Germany — to a German wine buyer.

Perhaps this betrays my own misunderstanding, or lack of understanding, but I think the closest comparison would be our own Napa Valley. Hear me out.

Both places are fertile landscapes with plenty of sunshine. Anne Krebiehl, in her provocatively titled book, The Wines of Germany, says that the Pfalz is Germany’s sunniest region; her chapter on the Pfalz is called “Sunny Abundance.” The Wine Atlas of Germany states that the region gets about 1,800 hours of sunshine, making it one of the warmest wine regions in Germany. Nearly every writer remarks on the exoticism and diversity of the agriculture here, with citrus, figs, almonds, and more.

Yet more than this, the heart of the Pfalz, the Mittelhaardt, is a mecca of wine tourism. Well-manicured estates line the famous Weinstraße, a road that runs north to south, beckoning visitors with generous wines, plump with fruit and flavor and sometimes a rather hefty dose of alcohol. Many estates here are quite large. Many estates have noble backgrounds (as in the Rheingau, there are lots of “vons” here). Many estates also have ownership structures that involve the very wealthy and business groups interested in luxury investing.

Any of this sound familiar, Napa?

Yet the Pfalz, at around 25,000 hectares (the second-largest wine region after the Rheinhessen), is also like Napa Valley in that it contains a multitude of narratives. There is no single “Pfalz” as there is no single “Napa Valley.” And if the more obvious luxury-agrobusiness vibe of the place is a bit dispiriting, for every 100 hectares of that, there are many hectares of small growers digging deeper into the true soul of the Pfalz.

In the far north, on the very border with the Rheinhessen, a veritable stone’s throw from Keller and Wittmann, the village of Bockenheim an der Weinstraße, with its gritty, blue-collar feel, has become something of ground zero for Germany’s viticultural avant-garde, with the Brand brothers and Andreas Durst taking full advantage of the cool climate and the limestone here to make wines that have an uncommon lightness for the Pfalz. About a half-hour south, in Kallstadt, both Koehler-Ruprecht and Müller-Ruprecht farm the famous pig’s stomach, the Saumagen vineyard, making their own distinctive expressions of this site.

Even in the heart of the Mittelhaardt, in the villages that look like they were pulled from children’s story books, with their timber-framed homes, tiny and asymmetrical and exploding with flower boxes and cobblestoned streets, there are smaller growers searching for the soul of the Pfalz, which seems capable of anything vinous: white, red, and sparkling.

In the south, Hansjörg Rebholz has proven that mineral-driven Rieslings could come from this place of “sunny abundance.” More recently, only about 20 minutes east of Rebholz, on the cold flatlands once thought to be suitable only for onions and potatoes, a young Lukas Hammelmann has taken this mineral-driven aesthetic to the extreme. His cutting, bracing, almost austere wines punch with the force of the Pfalz, in a satin glove woven from threads of the Nahe or even Saar.

My gut is that the luxury brands will keep on luxuriating — so it goes. But similar to most other regions in Germany, there are small estates searching (and finding) the truth of the soil and a younger generation returning to their families’ vineyards and finding their own voices. In doing so they will find the voice, the soul, of the Pfalz.

If this is a place that still confuses me, it’s a place I find myself wanting to understand better, to know better.

I’ve tasted quite a few wines over the last five-plus years that keep me very interested in what is happening here. That’s all the inspiration I need to keep on digging.