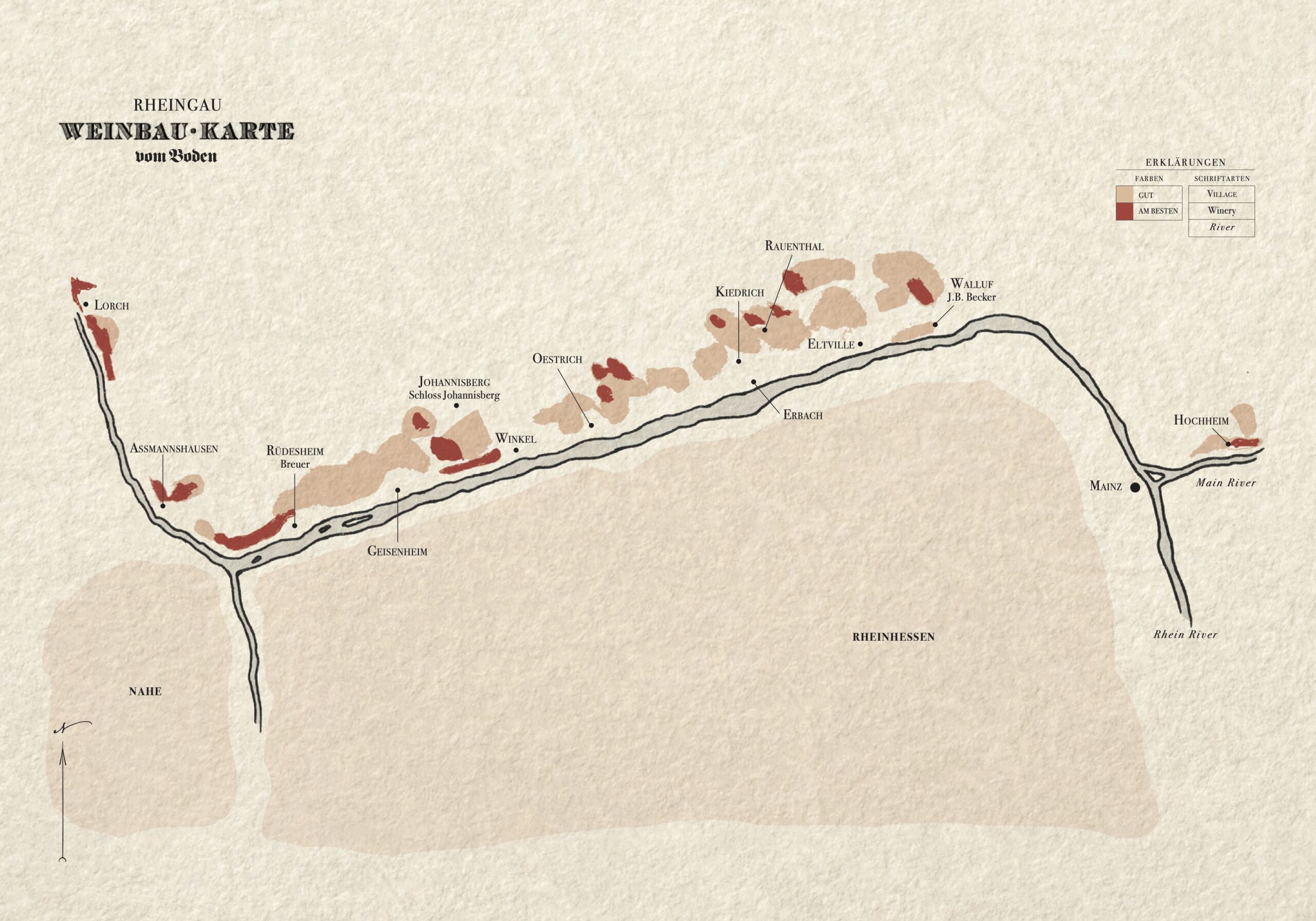

The Rheingau is shaped entirely by a short section of the Rhein River that, crashing into the Taunus mountains, is forced to veer sharply left (west), thereby creating this historic, south-facing slope.

The whole trip through the Rheingau, from east to west, is only around 30 kilometers (roughly 19 miles).

That’s the geography, fine. The more important question is: What’s the soul of this place about?

This is simplistic, I’ll admit, but I think it also offers a useful prism through which to contextualize the two most storied Riesling regions in Germany: If the Mosel is Burgundy, the Rheingau is Bordeaux.

The Mosel is full of small growers farming vineyards, the sites oftentimes more famous than the growers themselves. The growers weren’t, at least historically, a particularly wealthy lot. They were farmers. The historical fame of the Rheingau, on the other hand, belongs to the grand estates of the aristocrats. List the most famous Rheingau estates of the past few centuries and you have a laundry list of castles, monasteries, and aristocratic “vons”: Schloss Eltz, Schloss Johannisberg, Schloss Vollrads, Kloster Eberbach, von Simmern. While “Schloss” translates more to “castle” than to “chateau,” it’s close enough. You get the idea.

The Mosel is full of small growers farming vineyards, the sites oftentimes more famous than the growers themselves. The growers weren’t, at least historically, a particularly wealthy lot. They were farmers. The historical fame of the Rheingau, on the other hand, belongs to the grand estates of the aristocrats. List the most famous Rheingau estates of the past few centuries and you have a laundry list of castles, monasteries, and aristocratic “vons”: Schloss Eltz, Schloss Johannisberg, Schloss Vollrads, Kloster Eberbach, von Simmern. While “Schloss” translates more to “castle” than to “chateau,” it’s close enough. You get the idea.

The Rheingau, like Bordeaux, was in many ways the pioneer of a more considered and thoughtful viticulture. The growers of the Rheingau were the thought-leaders a century ago. The 18th century was something of a golden era for the Rheingau. The concept of holding back the top bottles emerged here. The idea of selectively harvesting certain grapes later, the “Spätlese,” was developed here toward the end of the 18th century. The fame of this region only grew through the 19th and 20th centuries, at least up to the 1960s and 1970s.

So far as I can gather, the historical fame of the Rheingau was based on richer, more amber-colored, sweeter Rieslings. This is in stark contrast to the Mosel’s rise to fame in the late 19th century and early 20th century, based largely on brisk, clear, yellow-green-hued dry Rieslings.

Curiously, if this history is accurate and the Rheingau was famous for off-dry Rieslings while the Mosel was famous for dry Rieslings, this narrative inverted itself toward the end of the last century. The story of the “Grand Cru” dry Riesling, the incredibly successful Grosses Gewächs or “GG” bottlings, championed and promoted by the grower organization the VDP, to some extent begins here in the Rheingau, with a movement to make dry and just-off-dry wines in the 1990s. This organization, called Charta, was started by Georg Breuer and Graf Matuschka at Schloss Vollrads. This movement later evolved into the first “great dry wine” category, called Erstes Gewächs. Then, even later, this evolved into the Grosses Gewächs or GG bottlings we now know from nearly all German wine regions.

I can think of no other single movement that has changed the perception of German wine so profoundly. The dry wine renaissance, born in an off-dry region. History is funny.

It must be said that while there are many positive associations to make between the Rheingau and Bordeaux, there are also some less positive associations. Both the Rheingau and Bordeaux, at some point, became more concerned with commercial enterprise than passionate viticulture. Both regions relied too much on the fame of the chateaux, the castles, and the family names to push sales while the quality of the wines decreased, in some cases dramatically.

Both of these regions, to some extent, just seemed to lose their mojo.

There are certainly some meaningful exceptions here. For me, the most obvious would be the estate of Georg Breuer, which continues to shape some of the grandest dry Rieslings from Germany, especially in cooler vintages. Peter Jakob Kühn is also a standout with plush wines of force and form. These wines showcase everything that the Rheingau can be: power, depth, texture, some polished roundness, all with elegance and definition.

It’s a lot to juggle, admittedly. But when you get it right, it’s quite a show.

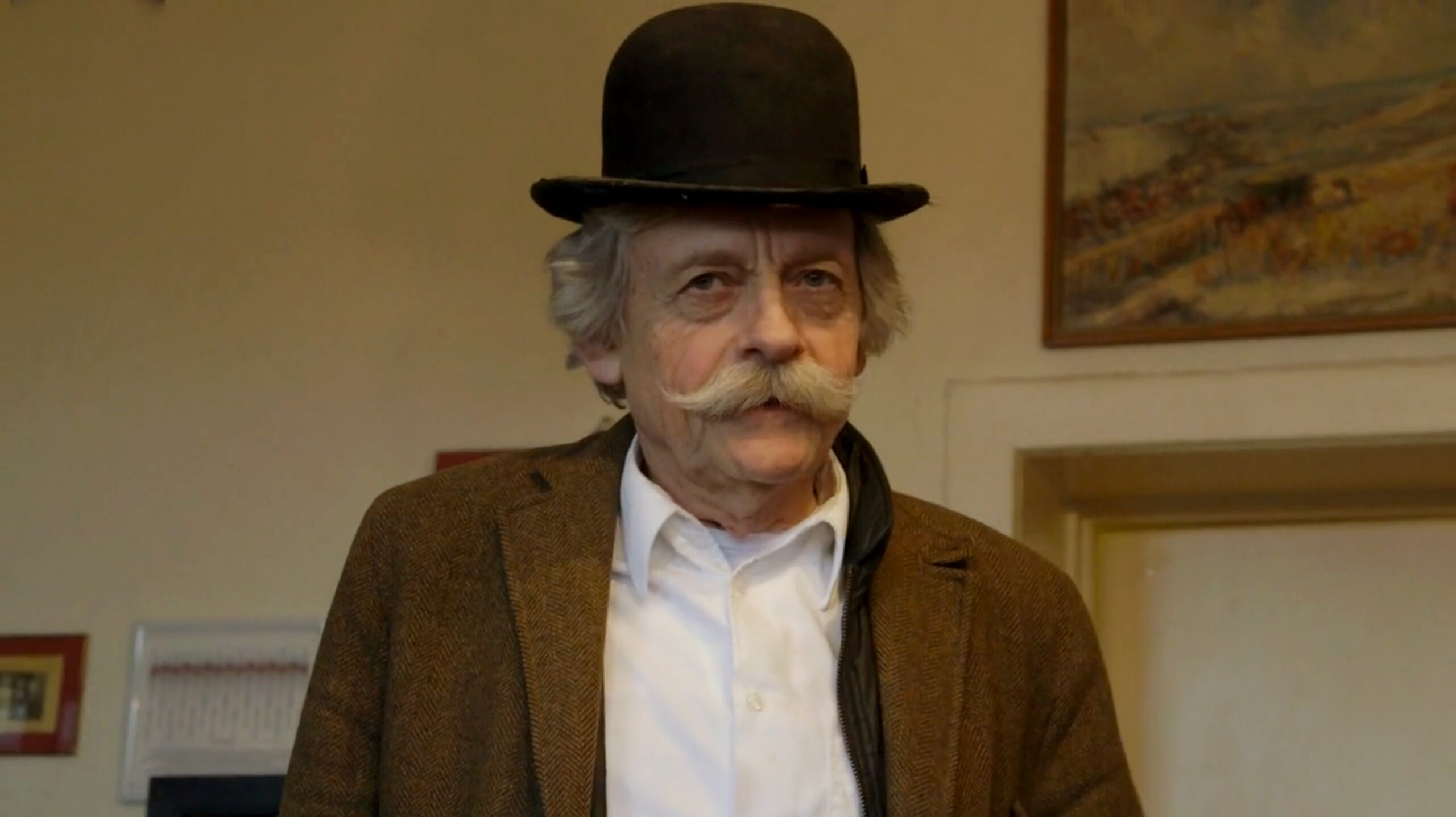

Now, you’d probably expect me to say something about the one Rheingau estate vom Boden works with: J.B. Becker.

That would be eminently reasonable, but I’m not going to — at least not here. While the estate of J.B. Becker is technically in the Rheingau, spiritually speaking, it is in truth in its own singular and spectacular universe, unlike any other estate in Germany I know of. There is not a sacred Rheingau tradition that this place hasn’t thumbed its nose at. Even the style of the wines seems to place them more in the Saar or Ruwer than in the Rheingau.

None of this makes any sense, of course, but Hans-Josef Becker doesn’t care what anyone thinks. Please read Becker’s producer profile on the website and try these wines if you can find them.