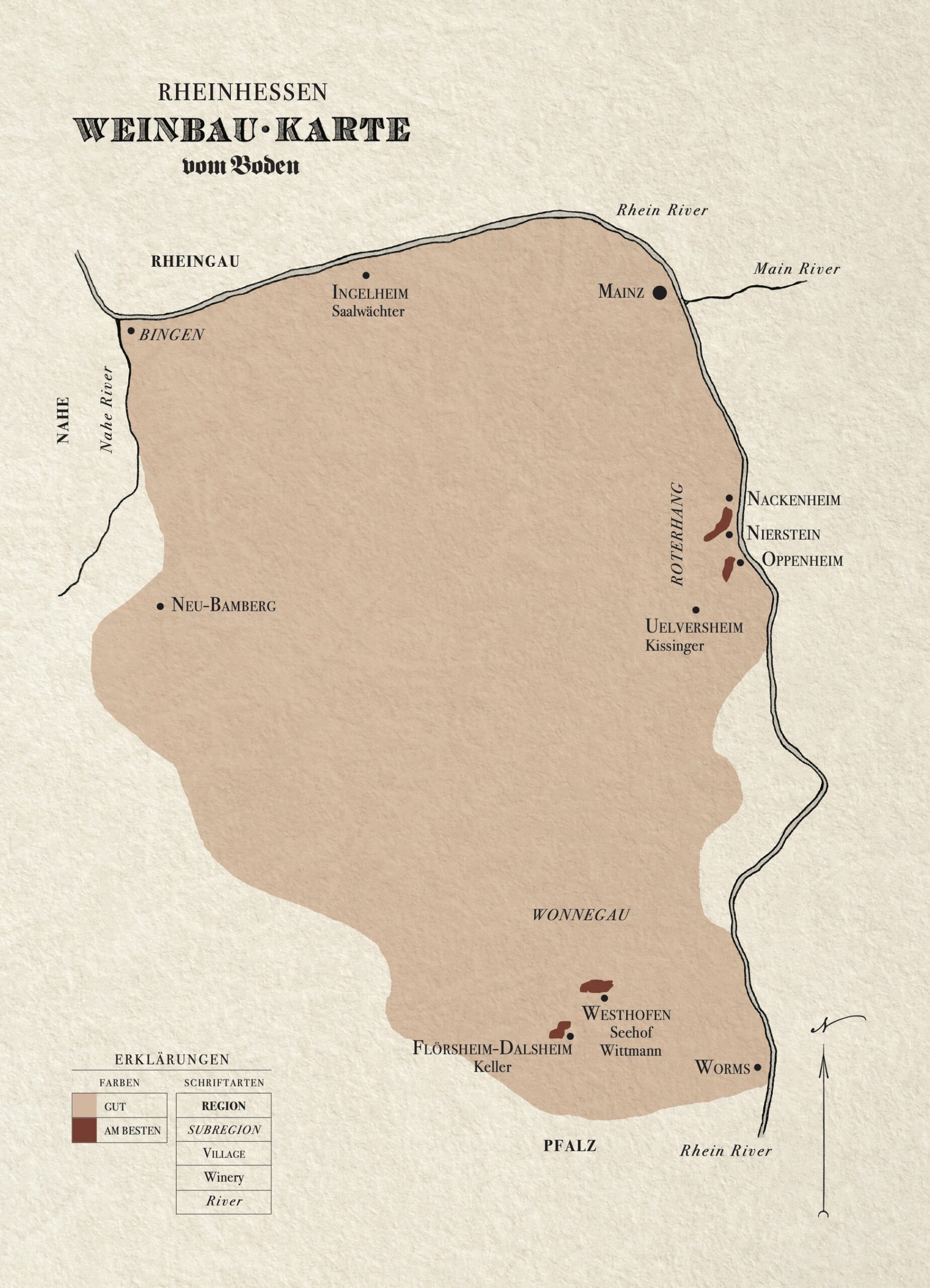

Think of the Rheinhessen as something of a square with its lower left corner lopped off. The Rhein River creates the northern edge, running from Bingen, where the Nahe empties into the Rhein, east to Mainz, where the storied river turns south, now creating the Rheinhessen’s eastern flank. The western edge is for a while defined by the Nahe, though the border of the Rheinhessen turns east around Bad Kreuznach and runs in a southeasterly direction to Worms, cutting off that lower left corner as mentioned and creating the southern border of the Rheinhessen as well, pushing right up against the Pfalz.

So how does one make wine-sense of a 68,000-acre squarish thing? The easiest first step might be to think of the Rheinhessen as having three key areas (and indeed, officially speaking, it does have three subregions): Nierstein in the northeast, the Wonnegau in the south, and Bingen in the northwest. Sorry, but my three regions and the official three regions don’t match, officially, as we’ll see below. Two of the subregions do line up, and for me two out of three ain’t bad.

I agree with the Nierstein subregion, which represents the top right corner of our square. Most wine people today refer to this place as the “Roter Hang” or “red slope.” The red slope name is, in the German fashion, wildly precise. This is a very steep slope — almost Moselle-esque — that pours down to the Rhein River valley to the east and southeast. And the soils here are red, what is generically referred to as “Rotliegendes.” In some books, this soil is described as compressed red sandstone, not slate, and in other books as a clay-rich weathered slate. So it goes.

The Roter Hang is the smallest subregion of the Rheinhessen, running roughly three miles along the river and then turning slightly west, away from the river and behind the town of Nierstein, from whence it gets its name. The vineyard roll-call here is impressive, at least for German-wine dorks: From north to south, we have the Rothenberg, Pettenthal, and Hipping, all of which were very famous even before Keller started farming small parcels in the latter two sites. As the slope bends away from the river, we have the final and less-famous sites Ölberg and Orbel, which nonetheless based on my recent tastings seem to have great potential.

The Roter Hang was, before the Keller revolution in the southern Wonnegau, the “blue chip Rheinessen” — something like my “Hollywood Mile” in the Moselle. The most famous Rheinhessen wines of the 20th century were made here. Queen Elizabeth, you may have heard, drank a Hipping Riesling at her coronation in 1953. While the Roter Hang is technically in the Rheinhessen, I have the sense that historically the wines of this place were thought of as similar to Rheingau wines, which is to say broader and more powerful, amber-hued and very often sweet. In the last 20 years this has changed, but some historical context never hurts.

I’m also in agreement with the second key subregion, the Wonnegau, sometimes referred to as the Hügelland, or “hill region.” This is the bottom-right corner of our square. The Wonnegau includes areas close to the Rhein River around the city of Worms, as well as regions farther west, away from the Rhine and up into the rolling hills. The most infamous vineyard in all of Germany is here, right in Worms near the Rhein: a relatively small, 13.4-hectare vineyard called the Liebfrauenstift-Kirchenstück. This was considered the greatest site in all of the Rheinhessen in the late 19th century. So savvy marketers, seeking to capitalize on this fame, invented the generic brand Liebfraumilch, perhaps Germany’s most notorious mass-produced, off-dry wine. In its heyday, in the 1970s and 1980s, it was made from all sorts of grapes from all sorts of places, from Müller-Thurgau to Kerner to blends of this or that from all over the Rheinhessen, Nahe, Pfalz, and beyond. While I think the name has little meaning to the youngest generation of wine fans, the fact that it took some 40 years for Liebfraumilch’s legacy to be washed away speaks to the power of its influence.

Regardless, the journey from historically infamous to contemporaneously famous is only a 15-minute drive some ten miles west, to Flörsheim-Dalsheim, well into the rolling hills of the Wonnegau. This tiny village is the home of Weingut Keller. There is simply no narrative of the Wonnegau, or of the Rheinhessen, or of German wine for that matter, that doesn’t have to spend some time here.

This is a cooler region, crawling west and away from the warming influences of the Rhein River. Here we have a rich diversity of soil, though importantly you’ll find a good amount of limestone. In the most generic of terms, this is the identity of this place. It is the bracing structure and thrilling glycerine-rich rush that limestone seems to offer, that Julia and Klaus Peter Keller have used to put this place not only on the map, but on the world’s short list of great terroirs.

This is a cooler region, crawling west and away from the warming influences of the Rhein River. Here we have a rich diversity of soil, though importantly you’ll find a good amount of limestone. In the most generic of terms, this is the identity of this place. It is the bracing structure and thrilling glycerine-rich rush that limestone seems to offer, that Julia and Klaus Peter Keller have used to put this place not only on the map, but on the world’s short list of great terroirs.

If Nierstein, with its Roter Hang, was unquestionably the most respected part of the Rheinhessen — the aristocrat in the room — from the late 19th through the first seven or eight decades of the 20th century, the history and fame of the Wonnegau goes back further. There was a warming period in the Middle Ages and during this time the vineyards around Worms, including Keller’s famous Kirchspiel, Hubacker, Morstein, and Abtserde, were treasured parcels of the church. Abtserde, as any German speaker will note, means “Abbot’s earth.”

For the last few hundred years, during a cool period, the Wonnegau was simply too cold to consistently ripen grapes. Obviously, since the 1990s, things have been warming up. It is one of the universe’s most fortunate coincidences that the very moment this region comes into the perfect zone for ripening Riesling grapes, some time in the late 1990s, the brilliant, young, and passionate newlyweds Julia and Klaus Peter Keller take over the Keller estate. The rest, as they say, is history.

The third and final subregion is where I have to deviate from the official line. The wine authorities say this third region is “Bingen,” a historically famous village in the far northwest of the Rheinhessen (the top left corner of the map). This is fair enough and without a doubt more erudite than my suggestion. I say the third subregion should just be called: “everything else.” We should leave this third region up for further investigation and possible further subdivision as the west and the central interior of the Rheinhessen begin to define themselves a bit more clearly.

Already there are some regional stirrings, some suggestions of where further delineations might be made. Ingelheim, the famous village in the center-north of the Rheinhessen, where Charlemagne built his palace, has ample vineyard land. Young growers like Carsten Saalwächter are showing us the potential here, especially in the north-facing vineyards riddled with limestone. Here, old-vine Silvaner looks across the river at its more famous Rheingau cousins thinking, perhaps, that now might be their time.

In the southwest, two famous sites circle the village Neu-Bamberg — Heerkretz and Höllberg. None other than Julia and Klaus Peter Keller have been, since 2021, working a tiny 0.2-hectare parcel in the Heerkretz. The parcel is a Clos, in fact, a walled vineyard with old Silvaner. There is no doubt Julia and K.P. were drawn here by the beauty of the place, but also because of the unique soils, a curious shell limestone over dense volcanic soils. This region, pushing up against the Nahe, shares some of the famous complexity of the soils of the Nahe, with patches of limestone, sandstone, porphyr, and more. Finally, just in the western shadow of the Roter Hang, we have growers like Moritz Kissinger in Uelversheim, experimenting with Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Weissburgunder, Pinot Noir, and more in a wildly compelling style that combines natural and classic winemaking, taking full advantage of very cool limestone sites only now coming into a perfect ripening zone, much as the Kellers did some 20 years before in the Wonnegau.

One thing you can say about the Rheinhessen: There is a lot of land here, a lot of vineyards, and a lot of growers without a clearly established identity — yet. You might have noticed that the entire center and western edge of our Rheinhessen map is curiously blank. This will change quickly. Further articulating these places and organizing this cacophony of estates and vineyards will be the work of the next few decades.

Yet this much is wildly obvious: There is a lot to be excited about.