Writing something on the Saar is a daunting task. This is one of the most sacred landscapes for Riesling.

In theory, if not always in practice, the wines of this valley are among the most austere, the most steely, restrained, and mineral-driven Rieslings on earth. Very few wines, Rieslings or not, ever achieve the angelic, high-toned notes that are the essential center of a great Saar wine.

While more recent treatises on German wine seem to have simply lumped the Saar into the Mosel, following the bureaucratic model, earlier books often featured love letters to the Saar. In Frank Schoonmaker’s inspired book The Wines of Germany, he writes: “Wine experts, after the fashion of sailors, are supposed to have their loves in every country, and to promise undying fidelity to each one, impartially, every time they taste it. But with all due respect to Chateau d’Yquem and to Montrachet, to Marcobrunner and Imperial Tokay, I still say, give me a perfect Scharzhofberger of a great year.”

He continues, with one of my favorite lines in all of wine writing: “In these great and exceedingly rare wines of the Saar, there is a combination of qualities which I can perhaps best describe as indescribable — austerity coupled with delicacy and extreme finesse, an incomparable bouquet, a clean, very attractive hardness tempered by a wealth of fruit and flavor which is overwhelming.”

Over 65 years later, to my mind, no better line has been penned to capture the essence of a great Saar wine.

In fact, a serious Saar wine can have such a unique signature that it’s not uncommon for an experienced taster to use the word “Saar” as an adjective. As noted in the Nahe regional writeup, the top wines of the upper Nahe can have a certain Saar quality. Certain cooler Mosel vineyards — such as those around Thörnich or Traben-Trarbach (think Ludes or Weiser-Künstler) — can have a certain Saar quality. More than one taster has noted that most of our Mosel growers have a Saar aesthetic, and this is unquestionably true. Sorry, at the end of the day, my palate is maybe a bit too tidy in its demands.

In any case, whenever this adjective is used, you can be sure it is a compliment.

While the Mosel, Saar, and Ruwer are all administratively part of one all-consuming “Mosel” appellation, as I’ve stated before, this is total horseshit.

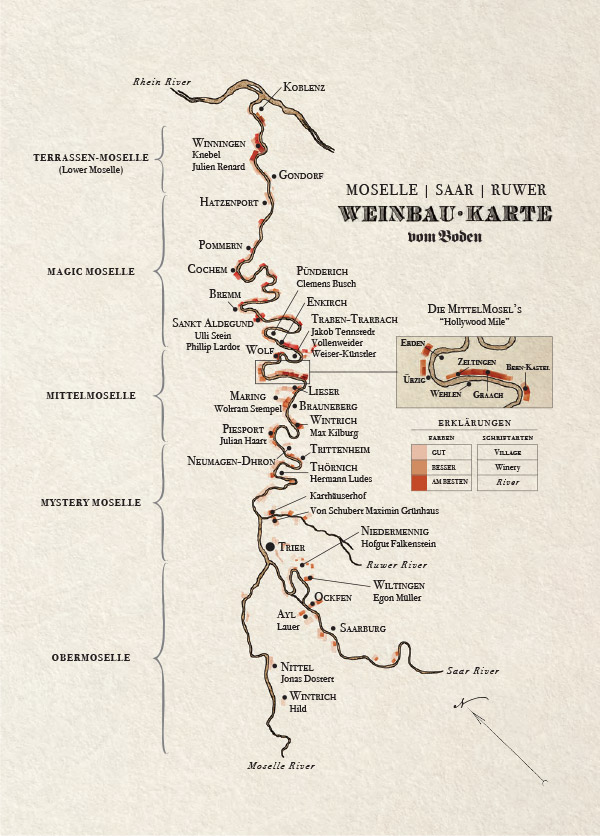

The Saar River and the Ruwer River are, in fact, two smaller tributaries that flow into the Mosel, essentially bracketing the city of Trier: the Saar on the southwestern side, just upstream, and the Ruwer on the northeastern side, just downstream. You can see these detailed on the map to the right.

If the Mosel is a large and grand region, and the Ruwer (as we shall read about) a tiny, pine-forest-dappled valley, the Saar is something in between. Even in scale, the Saar is in the middle. The grand Mosel has around 7,700 hectares, the tiny Ruwer only about 200 hectares. The Saar holds in its steely embrace almost exactly 800 hectares.

In a curious way, the Saar, which can produce among the most startling of all white wines, is (with a few exceptions) not a particularly startling landscape. It is a much more open valley, with flattish, rolling hills, a bit in flavor like the Obermosel or even the Rheinhessen, albeit with some curious outbursts and dramatic inclines here and there. Even the Scharzhofberg vineyard, one of the Saar’s and Germany’s most famous sites, rises almost imperceptibly as you drive away from the village of Wiltigen into the side valley.

In many important ways, in fact, the Saar is very different than the Mosel. While nearly all of the vineyards of the Mosel cling to the banks of the river, the Saar is peculiar in that most of its greatest sites run away from the water: They are perpendicular to its edge. The Serriger Vogelsang, Ayler Kupp, Ockfener Bockstein, and Scharzhofberg all run away from the river itself. Push eastward away from the Saar, near Wiltingen and past the Scharzhofberg, and a crescent of vineyards around the villages of Oberemmel, Krettnach, Obermennig, and Niedermennig swings far into an open valley roughly four kilometers away from the river itself.

So what does all this mean?

So what does all this mean?

All this means that the vineyards themselves enjoy less of the moderating influence of the river; they are farther away from the warmth of the Saar itself. And while the Mosel is in some ways a closed system, with the furious winds of the high plateaus blowing right over the narrow valley, pushed away by the warm air off of the Mosel River, the Saar is a wide-open valley. It is windswept and cold. There is an old adage that I don’t totally buy, as generalities are often just alluring lies, but I’ll share it with you anyway: When the vintage is a bit too ripe in the Moselle, it is perfect in the cold Saar.

Either way, you can feel the cold in a great Saar Riesling: The blistering rush of Saar acidity is unlike anything else. It can make Chablis feel like a warm beanbag near a roaring fire. When the balance is perfect, it is a miracle — a gushing, ice-cold, bracing miracle dancing with pleasure, a hair’s breath from pain.

This can be a brutal landscape for the vine; this is a place that, historically, played with the razor’s edge of ripeness perhaps more than anywhere else on earth. As such, there were many misses.

Schoonmaker writes about the Saar, “The Germans have a saying that ‘in poor years the Saarwein is a beggar and in good years a noble lord.’”

One has only to look at the prices of Egon Müller’s wines over the last few years to realize the Saar is, these days, mostly a noble lord. In fact, with climate change, the Saar is becoming an interesting land for off-dry and more dry-tasting wines. Consider the explosive rise of Florian Lauer of Weingut Peter Lauer or Johannes and Erich Weber of Hofgut Falkenstein. Over the next decade or two, I expect this valley to become one of the most exciting places for dry Riesling and even Pinot Noir.